posts > security

Script Confusion: Playing with AppleScripts hidden in Named Forks

Intro to hiding compiled Applescripts in resource forks

I’ve been collaborating with sysop_host. He described a technique on hiding compiled applescripts in a file resource fork. In this blog, we’ll go through some interesting some implications of this.

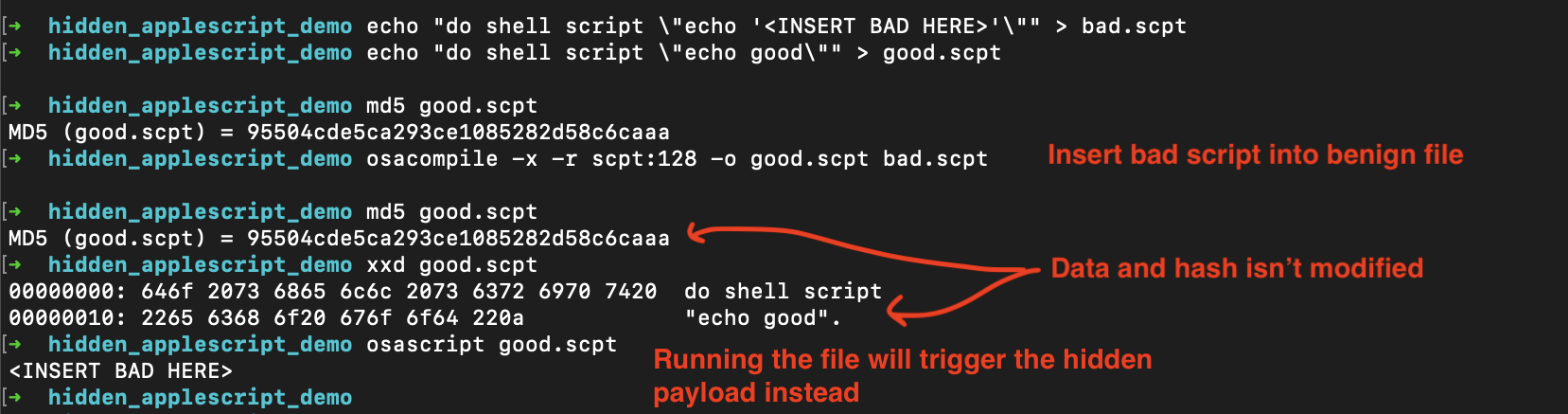

Below are some commands that will help illustrate the technique. (For more details see).

echo "do shell script \"echo '<INSERT BAD HERE>'\"" > bad.scpt

echo "do shell script \"echo good\"" > good.scpt

# 95504cde5ca293ce1085282d58c6caaa

md5 good.scpt

# Compile bad.scpt into the resource fork

osacompile -x -r scpt:128 -o good.scpt bad.scpt

# Should still be 95504cde5ca293ce1085282d58c6caaa

md5 good.scpt

# Inspect good.scpt (cat, strings, etc)

xxd good.scpt

# Running good.scpt will execute compiled bad.scpt instead

osascript good.scpt

The commands above do the following:

- Create two scripts

bad.scptandgood.scpt - Compile

bad.scptinto the resource fork ofgood.scpt - Inpsect the contents of

good.scptand see that both the data and the hash are unchanged - If you execute

osascript good.scpt, the hidden payload is what is executed.

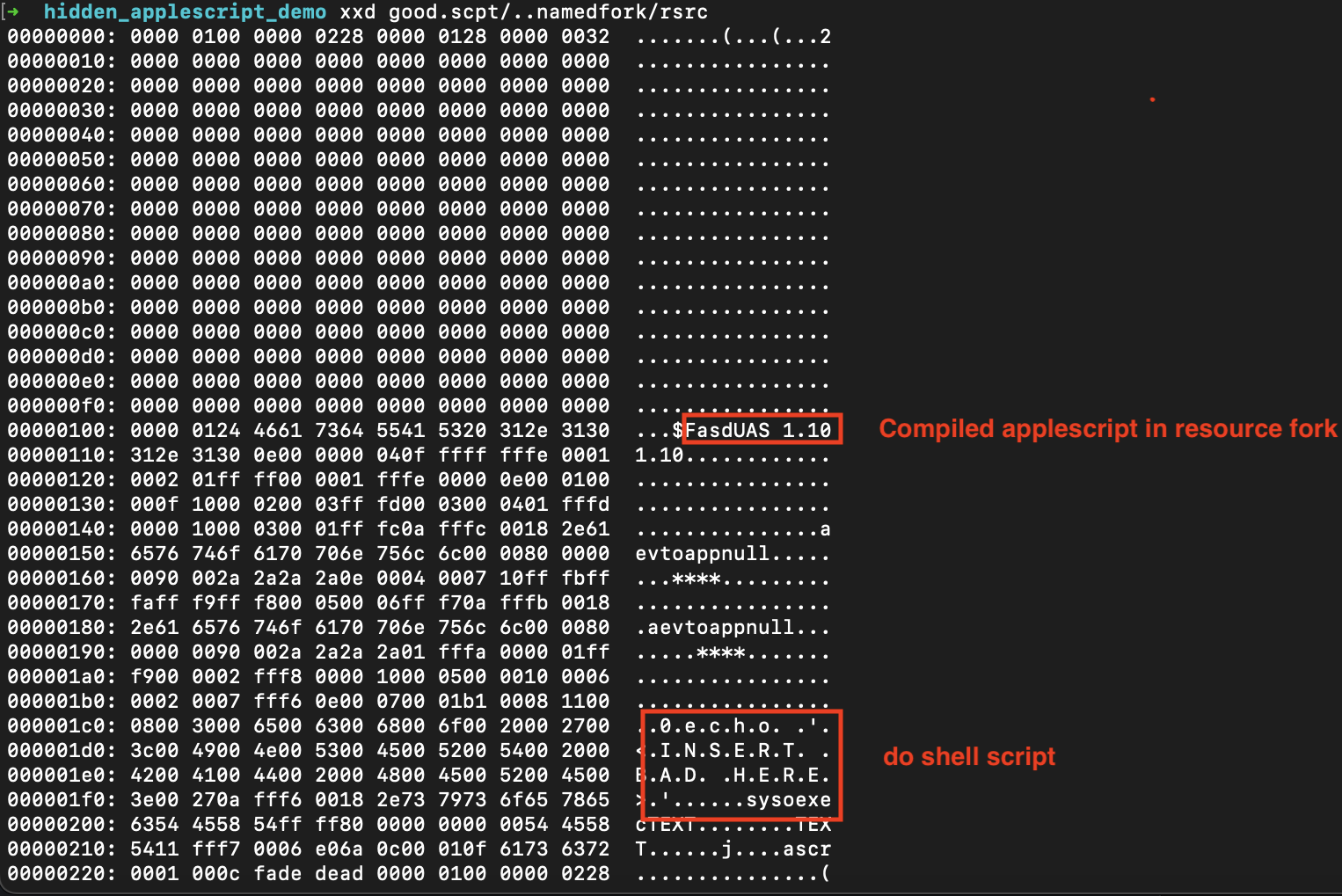

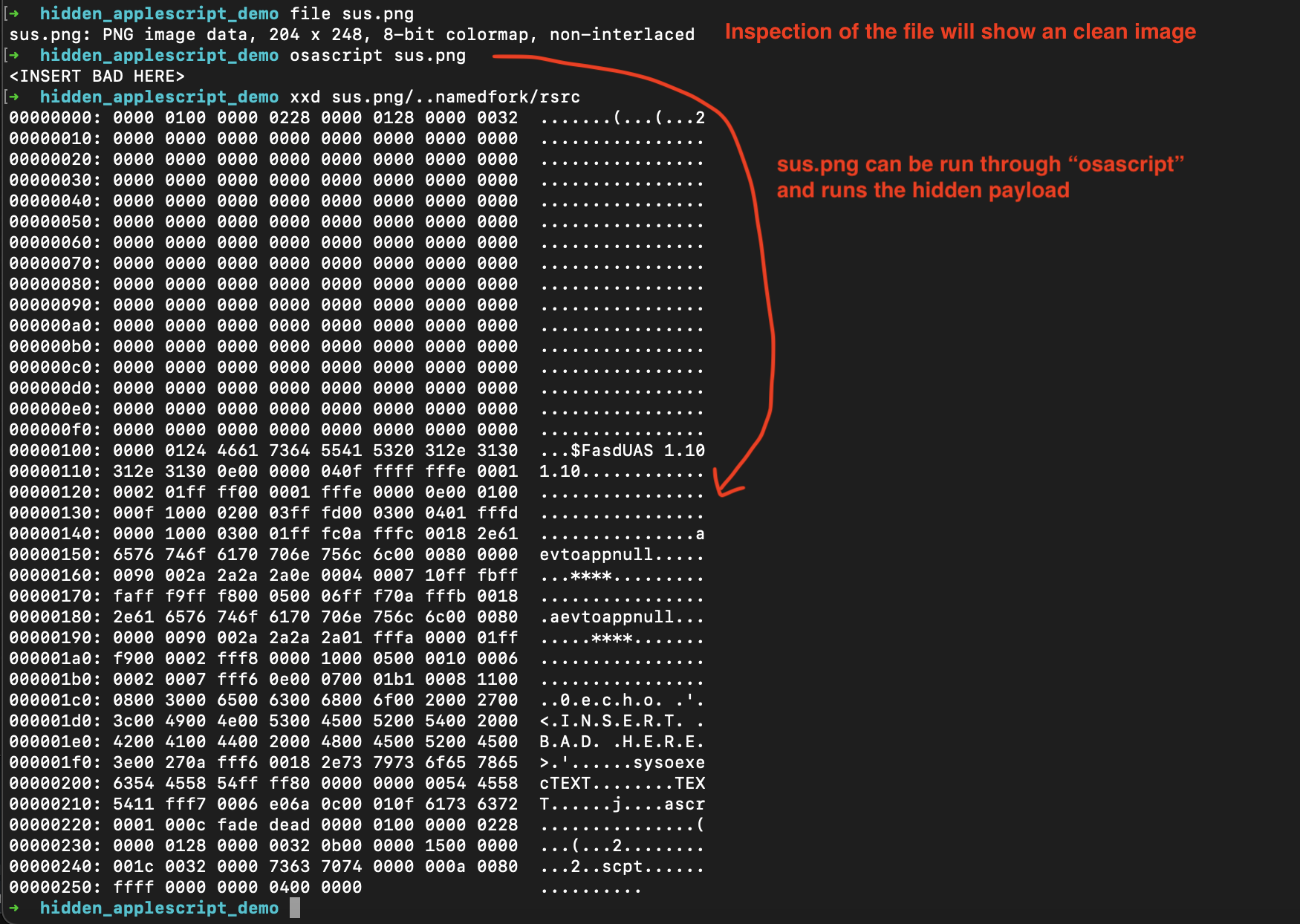

We can see the the hidden AppleScript in good.scpt/..namedfork/rsrc

The usage of named forks is not new. S1 has previously analyzed a sample hides a second payload in the named fork.. Another similar example is RustyAttr, where scripts were stored in the extended attributes. A notable difference between previous examples and this techinque, is that the payload doesn’t need to be extracted from the resource fork or extended attribute. It looks like osascript will automatically detect the hidden payload and execute it.

There isn’t a lot of documentation on this. Based on AppleScript Definitive Guide - Compiled Script File Formats the use of resource forks is a legacy feature that has been deprecated but supported for backwards compatibility. At the time of writing, our testing finds that the compiled applescript always takes priority over the original file.

With this, we will go through some observations that we’ve had while playing around this this.

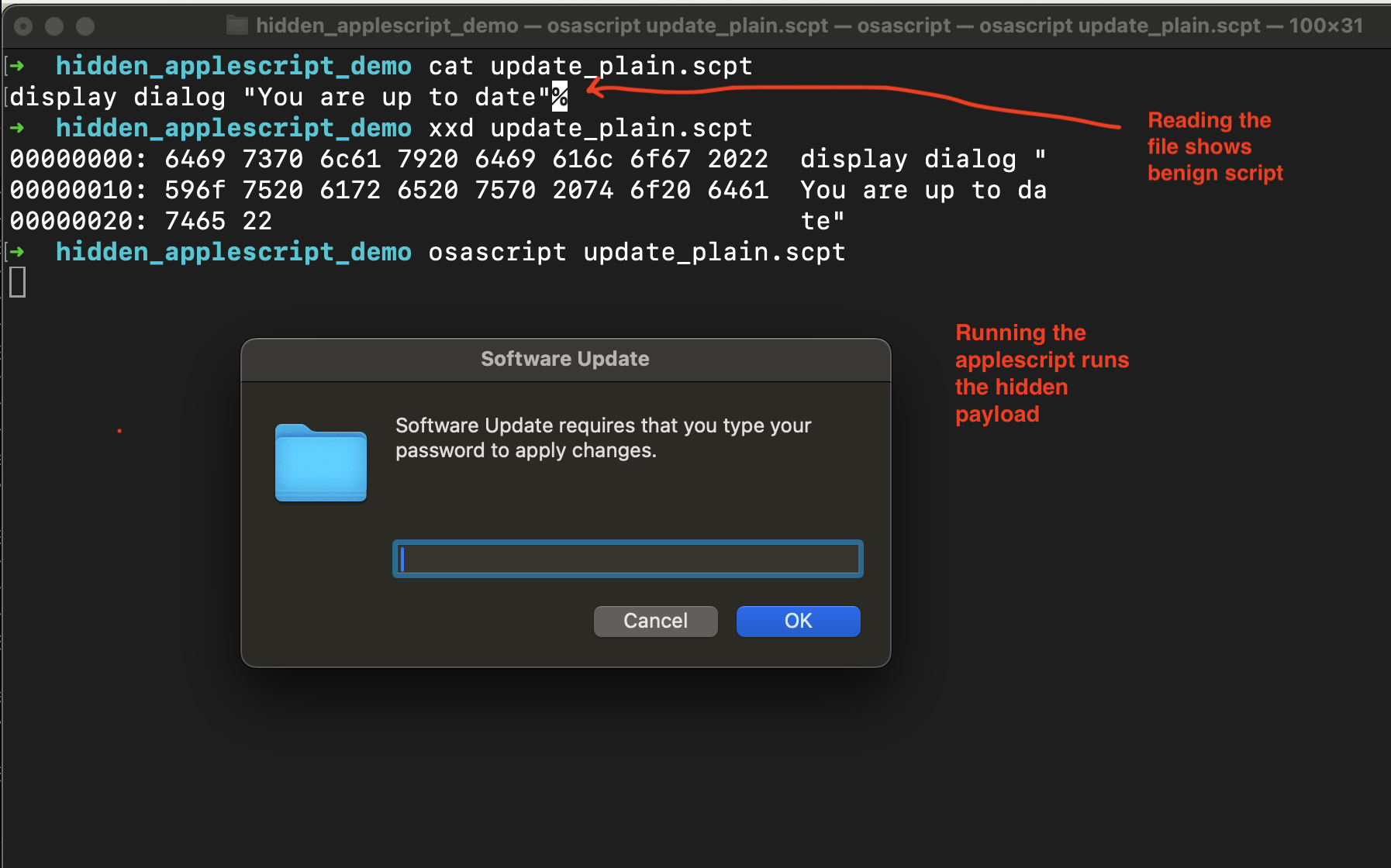

Example 1: Difference between read vs run

Similar to the example in the introduction, if the data in the file is another AppleScript (plaintext or compiled), this is ignored.

This can be an interesting gotcha since an analyst can find themselves analyzing some file, not knowing the the real payload is hiding in the resource fork. Moreover, if the analyst tries to upload the update_plain.scpt through the VirusTotal over the web UI, only the data fork will be be analyzed and the hidden payload is stripped in the process.

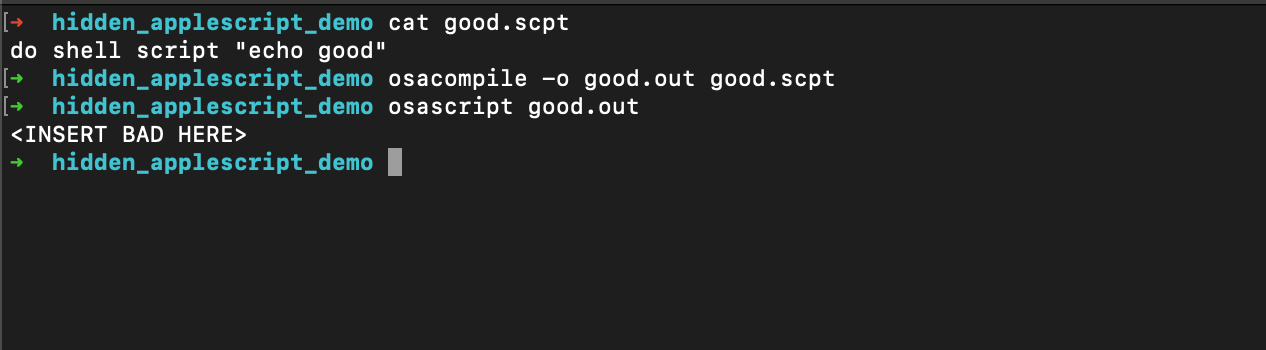

Example 2: Difference between read vs compile

Something we came across by accident, it looks like even osacompile prioritizes the resource fork over the data fork. The file you are inspecting in a text editor or IDE would be different from what is actually compiled by osacompile.

In this example, we use the good.scpt that already has the hidden applescript.

The compiled output differs from the source code

The compiled output differs from the source code

Example 3: Hidden in misc files

This method extends even to all types of files (images, pdfs, txts, etc). In the example below, if an compiled AppleScript is hidden in the resource fork of an image, then this image can be used to load and run applescripts.

osacompile -x -r scpt:128 -o image.png bad.scpt

osascript image.png

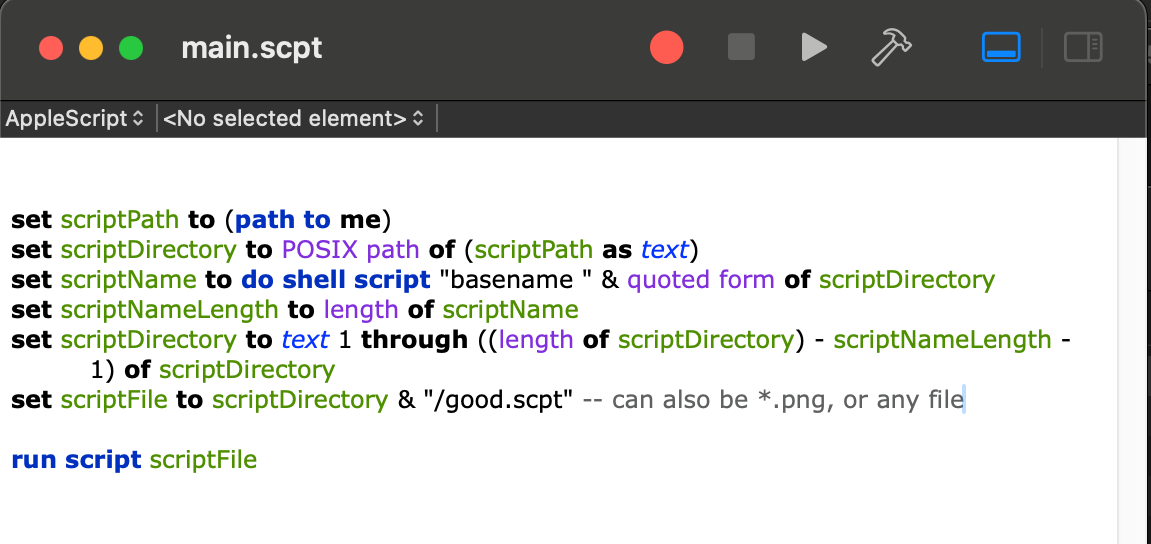

Example 4: Loading scripts

This is just an extension of case 1. Applescripts can load/run other applescripts using run script or load script -> run.

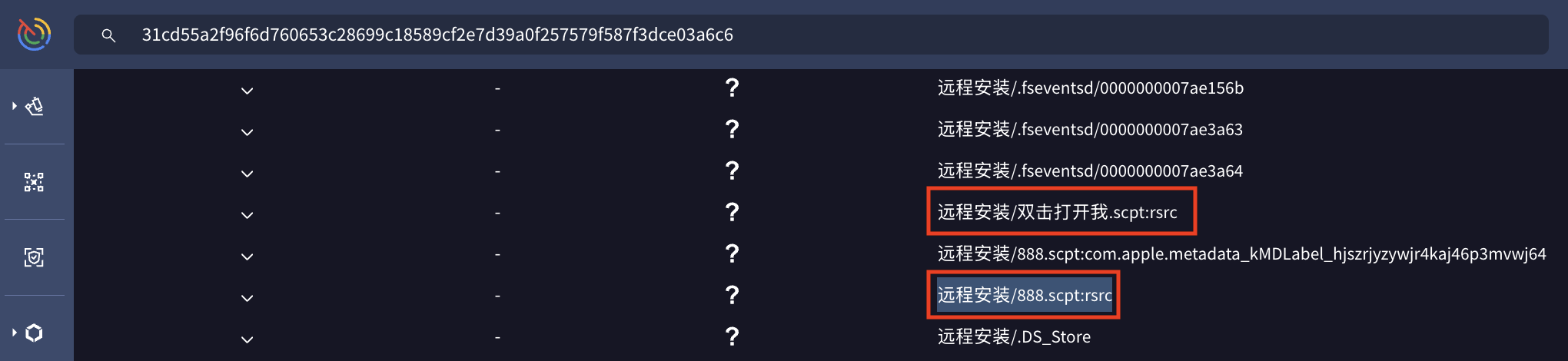

run script is used by this sample 31cd….a6c6. And if this DMG used this method, the analysis could have missed this since most analysis would have scanned the only data of the files

And in this example, the resource forks were not scanned (well they didn’t have anything)

Other notes

Unlike in S1’s sample and RustyAttr, malware that would use this technique don’t need to reference the <file>/..namedfork/rsrc directly since it’s all done implicitly. However, it’s not rare for compiled AppleScripts to have a resource forks. For example if a compiled AppleScript is created with Script Editor , it will have a resource fork. What is probably rare is compiled AppleScripts in resource scripts, but because it’s not common for these to be scanned, it’s hard for me to really say.

You can scan files with resource forks by

xattr -r <dir> | grep ResourceFork

You can try to scan resource fork directly

yara rule.yar <file>/..namedfork/rsrc

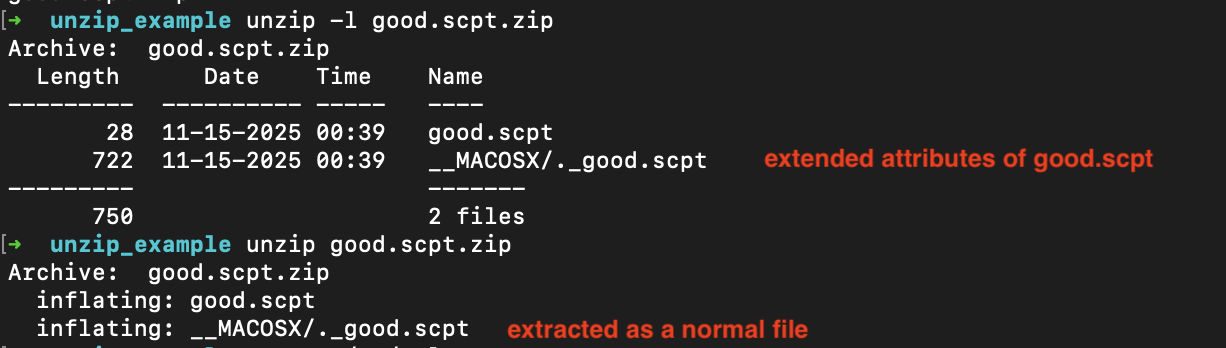

If you are analyzing a zip, use a tool that doesn’t set the extended attributes, like unzip.

Since the extended attributes are extracted as files, then they can be scanned like regular files. Note that the format of <file>/..namedfork/rsrc is different to __MACOSX/._<file>.scpt if its in a zipped file and <file>:rsrc if its in a DMG.

Be careful how you collect your artefacts. Some CLI tools like zip may strip extended attributes from the files while processing the files.

On top of what was suggested in the previous blog, I think, this just goes back to monitoring osascript and Script Editor behavior, and if in the future I encounter a sample where I the behaviour doesn’t match the what in the file, I’ll take a peak and see if there’s anything hinding in extended attributes or the resource fork.